The Coronavirus pandemic has revived interest in a Japanese mythological creature, with its symbol and stories trending on social media. Called Amabié (pronounced a-ma-bee-ay), the mythical mermaid-like creature is said to emerge from the sea and is considered an omen harking both good harvests and epidemics. The latter is all that was probably needed for connecting Amabie’s significance to today’s times.

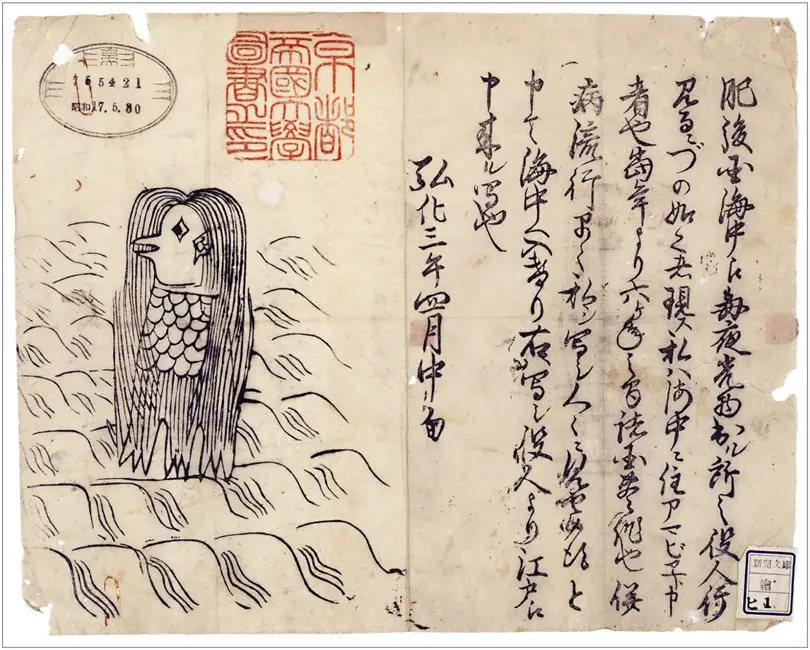

Part of Japanese culture since 1846, it was discovered in Higo Province (today’s Kumamoto Prefecture) when an unnamed officer went to investigate a strange light that had been appearing at sea, or so the story goes. Upon the ensuing encounter between the two, the strange creature explained, “I live in the sea. My name is Amabié. Good harvest will continue for six years. At the same time, a disease will spread. Draw me and show me to the people as soon as possible,” before submerging. The official drew a charming sketch and the episode was published in the ‘kawaraban’ – woodblock-printed bulletins of the time that featured news, outrageous gossip, and rumours.

Amabié is a part of a rich cultural history of Japan, with their folklore (yōkai) containing supernatural creatures, shape-shifting spirits or demons, some of which claim talismanic powers against infectious diseases. Yōkai characters, sans their historical context, are popular amongst Western audiences through the ubiquitous Japanese manga and anime series, whose viewership in Japanese audiences themselves cuts across ages and genres. They are also known through games such as Yu-Gi-Oh! and Pokémon, now a global children’s’ entertainment phenomenon.

It is said that some yōkai (now classified as yogenjū or prophetic beasts) appeared and predicted the future. In the 19th century, when the spread of information through kawaraban became popular, the practice of prophetic beasts for disease prevention using paintings of the creatures was adopted. The earliest recorded case is jinja-hime (or shrine princess) a creature with a serpentine fish body and a woman’s horned head. Said to have appeared in Saga Prefecture in 1819, she predicted an epidemic after 7 years of good fortune. Their proliferation in relation to outbreaks could have also been for economic interests. For example, during the cholera epidemics in 1858 and 1882, records show merchants selling old printed pictures of a three-legged ape-like monster. Prior to that in 1693, a rumour about a horse who predicted an epidemic and advised people to drink a decoction of berries and pickled plums as an antidote, was actually a ploy for raising the demand for berries and plums.

Translated description: A glowing object appeared every night in the sea of Higo Province [today’s Kumamoto prefecture]. When the town’s official went there and found something like the drawing, he was told, “I live in the sea. My name is Amabié. Good harvest will continue for six years. At the same time disease will spread. Draw me and show me to the people as soon as possible.” And [she] went into the sea.

This panel shows the official’s drawing that was sent to Edo [today’s Tokyo] in the middle of the fourth month, in the year Kōka-3 (mid-May, 1846).

Photo (shown as a cropped image) provided courtesy of the Main Library, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

However, by the 1918-1920 influenza epidemic, the popularity of yōkai in relation to diseases appears to have diminished, as there is no record of the creatures reappearing. Folklorists attribute this to government efforts in eradicating superstition as a part of its westernized scientific reforms, and a shift to mainstream media of mass-produced newspapers from kawaraban. As a result, it killed the culture of hand-drawn copying. However, Amabié (and other yōkai) never entirely vanished, appearing intermittently in manga, anime, games, and movies. Interestingly, Amabié was a particularly favourite yōkai of renowned manga artist and author Shigeru Mizuki.

The first tweet connecting Amabié to the COVID-19 pandemic appeared on January 30, 2020, and on February 27, 2020, yōkai artist Orochidō rekindled interest in the character, tweeting a contemporary painting, appealing to draw similar images. The tweet provides a timestamp for the current #Amabie phenomenon (if it didn’t start it), triggering the hugely popular #AmabieChallenge, that had the public drawing Amabié, aligning with the character’s original prophesy. There were 28 tweets with the term Amabié (in Japanese) on March 1, 2020; more than 1000 on March 4; a peak 46,000 on March 15; 10,000 to 20 000 almost every day in April; and 3000 to 10,000 per day in June 2020.

Amabié’s popularity now stretches from the northern islands of Hokkaido to the southern islands of Okinawa, appearing on posters at train stations, advising social distancing and avoiding non-essential travel. Many cities how have stand-up Amabié art exhibitions, with the character featured on sculptures, ceramic, glass, and textiles. Commemorative memorabilia and merchandise now include Amabié stuffed dolls, Amabié-shaped candies, Amabié-print sake bottles and Amabié T-shirts.

Importantly, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare has capitalized on the character’s popularity for public health messaging amidst the COVID-19 spread, besides recruiting manga and anime characters, including Kuaran, the government’s mascot for quarantine. Amabié is also a featured in the Japanese government’s Coronavirus contact tracing app that was released June 19, 2020.

The organic popularity of Amabié was a result of combination of an immense pandemic-induced interest, cultural history tied to infectious diseases and the ease of sharing on social media platforms at a time when many social activities are still limited. Last but hardly least, Amabié fits into prevalent Japanese manga and anime characteristics of kimo-kawaii (both ugly and cute at the same time) and heta-uma (poorly made at first glance but captivating). This may be why Amabié never entirely receded from public memory, and was destined for a comeback as a tool in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a time of rising anxieties and isolation during lockdowns, the cute 19th-century mercreature provides a comforting, playful, uniquely Japanese expression for connecting people, and possibly reviving the last vestige of a vibrant, rich culture to bind together the people of this tiny nation of islands.