A new report by researchers from the Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition Foundation (BCFN) and the University of Naples Federico II in Italy discovered that the Indian food is both nutritious and sustainable. The diet can be maintained by all without the need to sacrifice entire groups of food. The study analysed various edibles based on their effects towards physiological and planetary health.

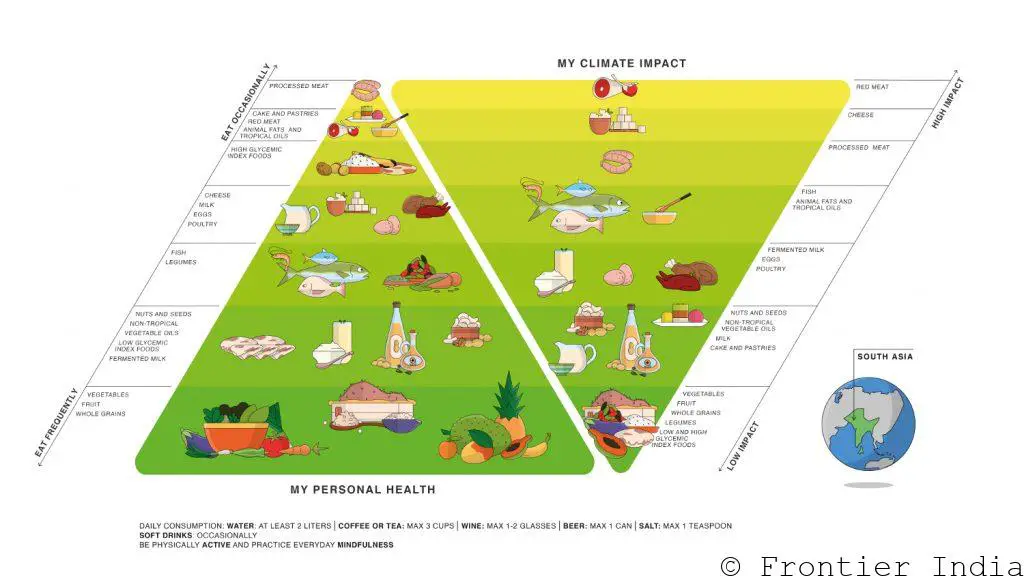

The food was ranked in order to design a “Double Health and Climate Pyramid” and was launched under the patronage of the Italian National Commission for (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) UNESCO. The study has been touted as a simple tool to guide one towards an optimum diet which reduces the risk of disease along with mitigating its impact on the climate, thus tackling two of the biggest humanitarian challenges in the 21st century.

The recommendation from the study calls for a sustainable and nourishing diet, which is plant based while including diverse sources of protein sources including legumes, nuts, fish, and poultry. The findings do not require moving away from red meat, dairy, or even cakes and pastries, however, indicate the frequency and the eating portion to meet health and sustainability targets.

Frontier India correspondent Aritra Banerjee spoke to Katarzyna Dembska, a researcher and nutrition advisor at the Barilla Foundation and one of the authors of the Double Pyramid report.

Q. In layperson’s terms, how does the common Indian benefit from the finding of your institute’s research?

Ans: The average Indian consumer can benefit significantly from the guidance of the Double Pyramid report for healthier and more sustainable diets. India is one of the world’s most impacted regions in terms of nutritional deficiencies, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes. The region is also at the center of the accelerating effects of climate change, experiencing more and longer periods of drought, whilst the ground water level in India has declined by 61% between 2007 and 2017, largely because of irrigation for food production.

Consequently, India has the most to gain from adopting healthier and more sustainable diets. Not only does the framework of the South Asian Double Pyramid guide the food choices for better personal health, but it also serves to lessen the impact of Indian diets upon the environment, helping us tackle the effects of climate change.”

Q. What piqued your institute’s interest towards pursuing research into the ‘Double Pyramid’ diet to begin with? Could you explain to our readers what the research process consisted of and why/ how are they relevant?

Ans: The development of the new Double Health and Climate Pyramid began with a recognition that our existing global food systems are failing to provide adequate and equitable food for all. Some 690 million people worldwide lack sufficient, nutritious food, whilst the proportion of children and adults who are either overweight or obese is increasing in almost all countries.

At the same time, these food systems are also posing an unsustainable burden on ecosystems and natural resources. Feeding the global population currently accounts for 21–37 per cent of our total net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which is a central contributor to climate change.

If humanity is to reset food systems from farm to fork, we must consider health and the environment side by side. The new Double Health and Climate Pyramid is offered as a tool to inform daily food choices and encourage dietary patterns that are healthy for humans and more sustainable for the planet. For the Health Pyramid, researchers clustered the most common foods consumed worldwide into 18 groups similar for their nutritional features and impact upon health.

These groups were then sorted into seven layers based upon their association with the risk of cardiovascular diseases, which are the most important cause of death and disability worldwide. The food groups associated with the highest beneficial impact on cardiovascular diseases are recommended more often, whilst those associated with a high risk are recommended occasionally.

For the Climate Pyramid, researchers calculated the median carbon footprint of the foods represented on the Health Pyramid throughout their production cycle, using a database created by the European Union (EU) funded project Su-Eatable Life. Together, this research forms the Double Health and Climate Pyramid, a simple visualization of different foods according to their impact on health and climate, helping individuals make healthier and more sustainable food choices.”

Q. Does the proposed double pyramid cater to the needs of seven different geographical regions? Given that India comprises of 29 different states, each with their own culinary customs based on cultural and agricultural differences, how will the ‘Double Pyramid’ survive the culinary and nutritional variances within different states?

Ans: The research produced in the report has been applied to different cultural and regional contexts, which includes seven experimental Cultural Double Pyramids for different regions to capture the full diversity of world diets. The South Asian Double Pyramid recognizes the vast diversity not just of culinary traditions, but also dialects, cultures, populations, and more, spanning as it does across the countries of India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and others.

Despite the challenge in defining a single South Asian ‘food culture’, a number of local and regional ingredients, preparations, flavours and textures shared common traits, which allowed researchers to build a Double Health and Climate Pyramid consisting of specific foods which are common and typical across the region as a whole.

These, among others, include rice, millet, lentils, ghee, mango, and leafy greens. In doing so, the South Asian Double Pyramid illustrates a clear example of a healthy and sustainable diet, one that can both apply to the region as a whole, but also be further adapted and applied to serve specific regional and cultural contexts, including the rich diversity of Indian cuisine.

What does the report say about the South Asian food and sustainability?

Starting from the base of the Health Pyramid, fruits and vegetables are recommended daily, and these are a constant presence in traditional diets. Leafy greens like mustard leaves, fenugreek, spinach and other vegetables like okra, onion, leek, cabbage, carrots, eggplant, turnip, tomato, cauliflower, bell pepper, and cucumber are widely grown. India is also a major world producer of fruit and is known as the world’s fruit basket. Among fruits we find mangos, grapes, apples, apricots, oranges, bananas, pineapple, jackfruit, guava, lichi, papaya, sapota and watermelons. Mango is one of the most popular fruits and can be consumed fresh, dried, or processed and is widely used in chutneys. Among whole grains, we find brown rice, millet, and sorghum, which used to be a major staple in central and southern India, brought from Africa to the region about 2,000 years ago for its excellent tolerance to drought, and is now regaining popularity. The region is indeed already experiencing an increase in the frequency and spatial extent of droughts, which will likely pose significant challenges for food and water security in India by depleting soil moisture and groundwater storage that provides an invaluable buffer. Bhutanese cuisine is characterized by the use of red rice, the only rice variety capable of growing at the high altitudes of this country. India is the second largest producer of rice, wheat, sugarcane, groundnut, vegetables, and fruit. Irrigation causes 89% of water abstraction, the process of taking water from a ground source, which has implications for the status of groundwater: the ground water level in India declined by 61% between 2007 and 2017.

Moving up the pyramid we find nuts like peanuts, cashew, pistachio, or almonds which are present in South Asian cuisine in curry dishes or as ingredients of sweets and desserts like rice puddings. Peanuts can be also mixed with black and white sesame seeds, dried coconut and jaggery, a form of unrefined sugar, into delicious traditional sweet balls while chia seeds are often mixed into yogurt and yogurt-based smoothies. Among vegetable oils, peanut oil, sunflower oil, and soybean oil are recommended and commonly used for high heat cooking and stir-frying, while sesame oil is characterized by a more particular aroma and is more frequently consumed as raw condiment. Palm oil and coconut oil are common too, but less frequent use is recommended due to their higher content in saturated fats. Consumption of palm oil and its derivatives has grown significantly over the last two decades, and about 70% of its demand is met through imports, mainly from Indonesia and Malaysia, where the land-use change associated with the expansion of oil palm is a major cause of deforestation and consequent carbon emissions

.

The consumption of milk and dairy products has been rooted in the South Asian tradition for many centuries, and the share of buffalo milk is around 50% of total milk production, as buffaloes are particularly productive in the changing climatic conditions. The health benefits of fermented milk have been documented by Indian Ayurvedic scripts dating back to around 6000 B.C. Yogurt and a yogurt-like curd are consumed in their plain form, and as aromatic sauces paired with meat or vegetable curry. Lassi is a popular yogurt-based drink made of a mixture of yogurt or curd, water, and spices and served salty, sweet, or fruity, like the popular mango lassi.

In western India, wheat is an important foodstuff, and Atta flour, a strong, high-gluten, durum wheat flour is the basis of breads like Chapati and paratha, just to name a few which are low glycemic foods, while baked roti can be considered moderately low glycemic. Chapati is a round flatbread made of flour and water: it is salt-free and meant to be paired with savory and spicy foods. It is torn off with the hands and used as a spoon to collect food. Legumes are recommended as one of the main sources of protein and form an important part of South Asia’s cuisines. The term dal indicates various types of dried lentils, peas, beans, and chickpeas cooked in a thick soup with onions and tomatoes and flavored with spices. India and Pakistan are the world’s top producers of chickpeas, probably introduced by Mughals into the subcontinent. Legumes can be used also in the form of flour in the preparation of foods like papadum, a crunchy flatbread used as a snack or side dish in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Hulled black mung bean flour is used, but also chickpeas and lentil flours are common.

Fish consumption is also recommended, and oceanic fish is abundant for the coastal area’s population, while freshwater species are available for inland dwellers. In Sri Lanka, 70% of the country’s animal protein supply comes from fish, and in Bangladesh it is the most commonly consumed animal-source food. Bangladesh ranks fifth among the world largest producers of aquaculture fish, in particular the shrimp industry is a great source of food and employment in the country, and the frequent use of freshwater fishes like butterfish and ilish is a distinctive feature of the country’s cuisine. Other consumed fish species in the subcontinent are king fish, seabass, Indian mackerel, white snapper, pink perch, and Indian salmon.

Moving up the pyramid we find poultry, recommended up to three times a week, and in South Asia chicken is by far the most widely consumed. It can be prepared in many different ways, like tandoori chicken, cooked in a tandoori oven, chicken korma, a creamy chicken stew, the savory chicken tikka or grilled. Chicken eggs are an ingredient in some regional cuisines and egg dishes are particularly popular among Parsis. Among cheeses we find paneer, which, unlike many other cheeses, is obtained by coagulation using lemon juice instead of rennet, making it completely lacto-vegetarian.

Moving further up the pyramid, we find high glycemic foods, such as rice, naan and potatoes. Because of their effect on glycaemia, limited consumption is recommended, favoring whole grain versions instead. Rice is the main ingredient of many common rice dishes like Biryani, which contains spices, meat, fish, eggs, or vegetables. Rice is more than a mere livelihood: it has shaped history, culture, art, and lifestyle. It is regarded as a sign of fortune and well-being, and plays a part in weddings, seasonal festivals, and rituals. Rice is a staple food for 70% of South Asia’s population, and food security is strictly linked to maintaining its stable prices. Because of its effect on glycemia, the whole grain version should be preferred. India has become the world’s second largest rice producing nation, with the largest rice harvesting area in the world, and Sri Lanka currently produces 95% of domestic requirement. The two countries, and Bangladesh, are among the most disaster-prone countries in the world, but despite recurrent floods, they have maintained steady production growth for the last three decades. According to the latest FAOSTAT data, emission of methane from rice cultivation causes about 15% of agricultural GHG emissions (in kg of CO2 eq.) in Southern Asia.

Widespread throughout central and southern Asia up to Iran, naan dough is very rich, and wholegrain flour is recommended: in addition to Atta flour, water, salt, yeast, milk, butter and yogurt are added, and the mixture is leavened and fermented. Naan bread can be served as an accompaniment, especially for meat dishes or soups, or buttered with ghee and soaked in tea or coffee for breakfast, or even stuffed with minced meat, nuts, raisins, vegetables, cheeses. Breads are then cooked either in the tandoor oven, on hot cast iron plates called tawa, or fried. Potatoes were introduced to the subcontinent by the Portuguese in the XVII century and used as ingredients in many dishes like the aloo gobi (potatoes and cauliflower flavored with spices) popular in Indian and Pakistani cuisine. Taro root, sweet potatoes, yam root and other tubers can also be found with some regional differences.

Among saturated fats we find ghee, which is one of the main cooking fats used in Asian countries and is obtained by clarifying butter at a high temperature. This process produces an almost anhydrous milk fat that can be preserved for months at room temperature and is used for frying in numerous Indian preparations.

Red meat is recommended occasionally, and includes mutton and lamb recipes like vindaloo or Bihari kebab. Processed meat is not common, but chicken sausages are eaten occasionally, and are found on the higher pyramid layer, to be eaten in moderation.