In India, well over 100,000 news publications were registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India on 31 March 2018. And around the world, hundreds of thousands of news publications exist. These news publications produce innumerable news stories each day, and with these news stories come visuals – photos adding the final touch to the news stories. In modern media, a news story is almost incomplete without these photographs. This is where photojournalists come into action.

Photojournalists and their contribution to news telling are often overlooked as our eyes hop onto the byline for who wrote the article, but we hardly ever look at who got the visual. As the name suggests, a photojournalist has to have the skills of both a photographer and a journalist to determine the highlight of the news story.

To get a better insight into Photojournalism and a photojournalist’s work, Frontier India News Network talked to Ms Ilana Rose, a professional photographer, photojournalist and author based out of Australia, who has been working in the field for over 25 years.

She graduated with a B.A. in Photography from the Victoria College of Advanced Education; Prahran Campus, Melbourne, Australia, which existed until 1 January 1992. After that, most of it became part of Deakin University. She also did ‘Red R Personal security and communications training (for humanitarians working in the field)’ and ‘Psychological first aid (for humanitarians working in the field)’.

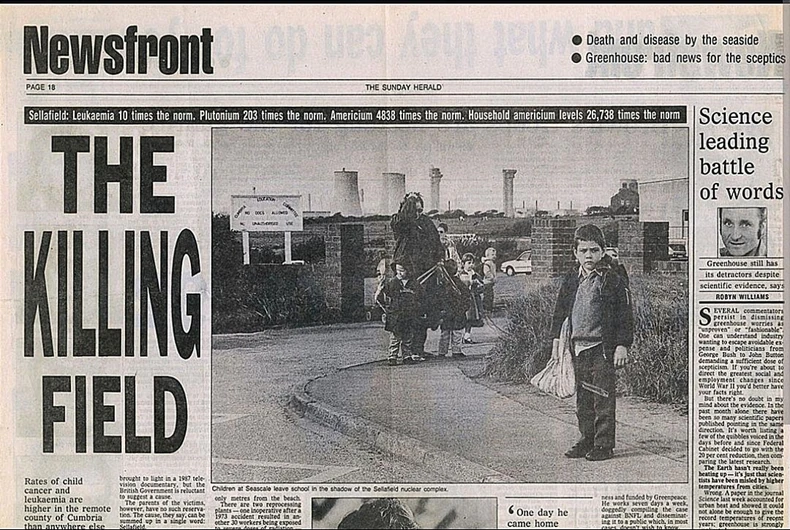

Over the past years, Ms Rose has worked for numerous media outlets and as a U.K. Foreign Correspondent for The Sunday Herald. Her work has appeared in major Australian publications including The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Weekend Australian Magazine, The Good Weekend, Who Weekly, Marie Claire and The Big Issue, to name a few, while clients have ranged from Victorian Government departments to arts organisations, record companies, NGO’s and film companies. Her work has been displayed at more than 25 exhibitions in Australia, China, New York and New Zealand and collected by galleries and arts organisations ranging from The Powerhouse Museum Sydney, The Victoria State Library, the City of Melbourne, SBS and Screen Australia.

In her conversation with FINN, Ms Rose talked about the nature of her work and what a photojournalist goes through to show the world what’s happening. Excerpts from the conversation are as follows.

Q. Very rarely have I come across friends or colleagues who want to/wanted to be Photojournalists. The perception is either photography or journalism. How did you come across to be a photojournalist?

Ans. I have always been interested in storytelling and visually documenting the world around me. I studied photography at school going on to study it at University and started working on local newspapers whilst still a student.

This led to working on some of Melbourne’s new Sunday broadsheet newspapers. As I was not a writer, I teamed up with a journalist that I had met whilst working on The Sunday Herald which allowed us to provide a complete package of both photographs and text, and I then went on to work as a foreign correspondent in England supplying stories for the Australian paper.

Q. What is the nature of the job? Being on the site of the incident is often open to risk, either physical or mental health. How does one go through, for example, clicking photos of dead bodies or mourning relatives of the deceased?

Ans. I primarily worked on long term feature stories rather than ‘hard news’ for the media, though as a news photographer I still covered demonstrations and significant events in my city, but I mainly concentrated initially on stories around youth, subculture, and music in my early career then I moved to documenting Social Justice issues.

Some of the bodies of work during this time certainly were challenging, for example spending years documenting graffiti gangs, the rave music scene and the plight of the homeless. On the whole, though, I felt no immediate threat once I had built relationships of trust with the subjects.

After I left the newspapers I worked with a leading NGO and travelled extensively to Africa, South America and Asia for nearly 5 years, capturing photographs and videos that were used for their marketing, websites and printed materials. I often led trips during this time, with external journalists for feature articles in Australian newspapers and magazines.

The trips that stand out, that challenged my mental health and physical well-being were while working in South Sudan and Uganda in the refugee camps and hearing the stories and seeing first-hand the horrendous atrocities perpetrated against the South Sudanese. The fighting was still going on and the danger levels were extremely high, but I had completed intensive training for communicators working in hostile environments, and always travelled into the danger zones with translators and community leaders that had extensive knowledge of the warring factions.

I also travelled to Rwanda for the 20th anniversary of the genocide meeting and photographing survivors and to Ethiopia for the 30th anniversary of the Famine. It is impossible to forget the trauma that the people in all of these places live with, but the fact that they trusted me to bring the horrors that these communities survived through to the notice of the general public via my photographs has given me strength and a huge appreciation of the safe and comfortable life that I lead in a country like Australia.

Q. For you personally, what was the toughest story as a photojournalist?

Ans. Without a doubt, my work in South Sudan was the toughest story that I worked on as a photojournalist. I photographed so many unaccompanied children that had witnessed their families being killed as they attempted to escape the carnage and had walked for days to find safety. I documented them as they crossed the border and were given emergency energy biscuits as they hadn’t eaten in days, and then travelled with them by truck to the refugee reception centre 80km away in Northern Uganda. These children were between 8-12 years old, the same age as my own son was at the time and it broke my heart to have to leave them behind with no one to look out for them and so little hope for their futures, with some of them begging me to take them home with me.

Q. Are there any misconceptions or stereotypes about Photojournalism that you’d want to address?

Ans. I think that the image of Photojournalists is that they are hardened and sometimes lacking sensitivity and that it is all about the adrenaline hit that they get when on assignment. It would certainly be true for some, but most do it because of the need to make the general public aware of issues, show the truth of a situation and the empathy that they feel towards the people whose stories that they are telling.

Q. Anything else you’d like to add?

Ans. I feel so fortunate that through my photographic work I have had the ability to give a voice to those that are under-represented and bring attention to stories that the general public might not be aware of.