Two consortia of European nations are developing a programme for the Future Combat Air System. The British-led initiative is advancing more rapidly than the Franco-German one, but both still need to be completed, which looks like a difficult task due to internal squabbling.

Six European nations have opted to develop a Future Combat Air System and enter the competition for next-generation aircraft over the past five years. On the one hand, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Sweden are creating TEMPEST, a system of systems centred around the eponymous fighter. On the other hand, Germany, France, and Spain have committed to developing a Future Combat Air System (FCAS) that includes a New Generation Fighter (NGF). The two programmes will be created within a comparable timeframe, but their technical characteristics, particularly their status, will not be the same.

TEMPEST

The United Kingdom, Italy, and Sweden planned to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in December 2020 to create a next-generation fighter. This was to take place at the 2018 Farnborough Air Show after the display of a full-scale concept model. The paper addressed R&D cooperation and established a €6 billion, equally shared programme conceptualisation. A Concept and Assessment Phase is also scheduled to commence in 2021, followed by a complete development phase in 2025. Initial Operational Capability (IOC) is anticipated for the TEMPEST fighter at the programme’s core by 2035.

In July 2021, the British Defense Minister signed a £250 million (€295 million) contract with the so-called Team TEMPEST, composed of BAE Systems, Rolls Royce, Leonardo UK, and MBDA UK. This marked the on-time start of the Concept and Assessment phase, primarily concerned with developing suitable sensor fusion. The intention is to equip TEMPEST with the ability to serve as a flying C2 node for other assets operating within the same system of systems, similar to how Lockheed Martin’s F-35 fighters function.

As stated by British officials at the 2019 DSEI conference, lessons acquired from this and past development programmes will be taken into account. At the 2021 DSEI show in London, a TEMPEST fighter model and two unmanned jet models designed to fly in formation were unveiled. In statements given at the time, British experts underlined that participating companies were in no hurry to fly a demonstrator or finalise the design. Instead, the team concentrated on developing relevant technologies and capabilities through model-based system engineering and design. Air Commodore Jonny Moreton, the director of the future combat air programme for the Royal Air Force, stated on that occasion that the “digital engineering revolution” will help “break the forty-year cycle” typically required for the conception, development, and construction of a new programme, thereby reducing the development cycle to ten to fifteen years. Team TEMPEST will also consider ways to “future-proof” the programme to maximise its effectiveness. The objective is to overcome one of the major challenges that typically plague complicated and lengthy development programmes: operational requirements are typically determined early on and then taken for granted, meaning that aircraft may be obsolete by the time they are fielded.

By enhancing the role of digital technologies, TEMPEST partners aim to incorporate ambitious experimental systems while controlling costs and adhering to timelines. According to the corporation, Leonardo UK will be in charge of the Multi-Function Radio Frequency System (MFRFS) data gathering protocols, which are predicted to be “four times as accurate as existing sensors in a package one-tenth the size.” The onboard processing suite of the MFRFS will enable the filtering of combat data to build a dynamic picture. The Italian company’s British division will be responsible for exploiting and repackaging commercial technology, such as 5G networks, minimising the size and weight of sensors and the energy required to power them.

Tempest Features

Team TEMPEST is also charged with developing a wearable cockpit interface to replace analogue and digital inputs with an augmented reality display powered by a network of Artificial Intelligence (AI) capabilities.

Rolls Royce is developing the “Integrated Power System” (IPS), a hybrid system that will combine gas turbines and electrical systems. The IPS will function as a “flying power plant” for sensors, avionics, and directed energy weaponry. The engine is designed to generate electrical power that is ten times that of the Eurofighter TYPHOON. The design of heat fluxes and hotspots will utilise AI simulator technologies. According to the business, artificial intelligence, simulators, and hardware testing might cut development time in half.

In addition to hypersonic missiles, unorthodox technologies may also be incorporated into the arsenal, which might include directed energy weapons. Project Alvina, which is focused on establishing the scheme to deploy small drones in swarms, and the Intrepid Mind Robotics’ MOSQUITO airframe allows five distinct wing shapes to be interchanged with a fuselage in 10 minutes, have also made progress.

Tempest Costs vs Benefits

In 2021, a Command Paper was submitted to the British Parliament reiterating that the TEMPEST fighter will be one of the most important acquisition programmes during the following decades. On the one hand, the country can utilise its industrial foundation to establish a system centred on the United Kingdom. On the other hand, it will aid in the modernisation of the base since disruptive technology will accelerate production while reducing costs. According to a report by PWC, the plan will have a major influence on the British economy, with a contribution of £26.2Bn (€30.8Bn) between 2021 and 2050, which is expected to reach £100Bn (€118Bn) when partners and the supply chain are included. In addition, the initiative is expected to serve around 21,000 employees annually.

The United Kingdom has funded nearly all of the initial phases of this cooperative programme. Following the 2018 MoU, the Italian multiannual defence planning document (Documento Programmatico Pluriennale Della Difesa) for 2021-2023 allocated €2 billion to the program’s research and development. However, the sum will be spread over the following fifteen years, with only €60 million to be committed in the next three years and the largest payment slated for 2027.

Regarding Sweden, Saab, as the primary contractor, established a centre of excellence to investigate pertinent technologies in 2020 and was recently commissioned to conduct preliminary studies regarding the development and implementation of future combat air capabilities. However, the € 24 million contract signed with the Swedish Defense Materiel Administration (FMV) on June 1 is meant to benefit the joint programme with the United Kingdom and Italy and the GRIPEN fighters developed domestically. Stockholm has not yet committed to participating in the TEMPEST fighter’s development.

The United Kingdom may be obliged to reorganise its purchase priorities, particularly concerning the F-35 programme. As the lone Level 1 partner, London was anticipated to purchase 138 fighters, but only 48 have been ordered. The Department of Defense is anticipated to place more purchases, but the total number of units may exceed expectations.

The Franco-German-Spanish FCAS Programme

While the United Kingdom is making good progress and staying on track with creating the TEMPEST programme, the FCAS needs to catch up due to disputes between its major industrial partners.

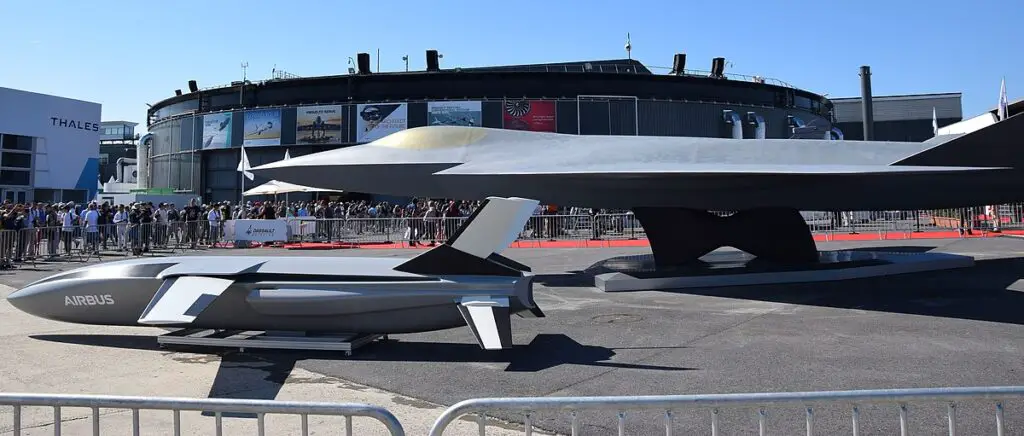

In 2017, France, Germany, and Spain reached an agreement on the construction of a cooperative Future Combat Air System (FCAS), with the first technology demonstrators anticipated in 2026, then pushed back to 2027, and final commissioning scheduled for 2040. In February 2019, Berlin and Paris inked a €65 million two-year Joint Concept Study, and Spain joined the plan a few months later. Due to diverging political priorities between France and Germany, the launch of the 18-month, €155 million Demonstrator Phase1A, which is essential for the development of the New Generation Fighter (NGF) and is at the core of the FCAS system-of-systems, was delayed by one year, occurring in April 2021 instead of April 2020. To maintain the 2027 timetable for the first demonstrators, partner countries needed to quickly reach an agreement on Demonstrator Phase1B, which would expand on the previous phase and signal Spain’s official entry into the programme.

In May 2021, France, Germany, and Spain concluded their intergovernmental negotiations by pledging €1.2 billion each for Phase1B, which will last through 2024. They agreed to continue their collaboration and launch Phase2, with investments of up to €8.6Bn (or potentially more) through 2027, when it is anticipated that a demonstrator will be ready. However, the contract that key firms and the French directorate general of weapons (Direction générale de l’armement, DGA) are expected to sign defining the conditions and funding scheme for this phase has not yet been completed, putting the entire program’s completion at risk.

Squabbling Partners

The administration of intellectual property rights is at the centre of the 1A Phase dispute. After Spain joined the programme, Germany sought access to all co-funded research in light of increased Airbus involvement, but Dassault Aviation refused to share expertise gained during the development of other programmes like RAFALE. The detailed listing of all intellectual property rights that must be shared to complete cooperative projects allowed for resolving conflicts and initiating this phase. Similarly, the workflow allocation is the primary source of the impasse in Phase1B. According to reports, Airbus is preventing the finalising of the contract of this phase as it seeks an equal involvement with Dassault in creating the fighter without compromising other technological pillars. Fighter (New Generation Fighter(NGF)), combat cloud, engine, sensors system, remote carrier, missile system, and stealth are the seven technological components that make up the FCAS programme.

Using the “best athlete” premise, each will be led by one of the three primary contractors. Dassault Aviation was initially tasked with developing the NGF, with Airbus Defence and Space as its primary partner. The German corporation is the market leader in the remote carrier, combat cloud, and stealth technology. The European Military Engine Team (EUMET) is responsible for the engine alongside the Spanish subsidiary of the Rolls-Royce Group, ITP Aero. EUMET is a 50/50 joint venture between the French corporation Safran and the German firm MTU.

Due to the partial overlap of contracts for the various pillars, the entire programme is experiencing delays, and real progress may only be observed on the engine. In January of last year, the DGA said that the prototype engine developed from the Snecma/Safran M88 currently powering RAFALE’s fighters had undergone successful testing with the use of heat-sensitive paint Thermocolor, which allows it to detect temperature based on colour changes.

Viability of merger of the two programs

General Luca Goretti, chief of staff of the Italian Air Force, stated in November 2021 that the TEMPEST and FCAS programmes might eventually integrate. The programmes share a similar anticipated delivery schedule (between 2035 and 2040) and are both influenced by the system-of-systems philosophy of the F-35.

Pros for Merger

Britain and Italy, as Level 1 and 2 partners in the US-led F-35 programme, respectively, have some of the most relevant industrial and “philosophical” experience in 5th generation fighters among European countries. British companies are responsible for creating or developing 10 to 15% of each fighter’s components. For instance, BAE systems and Lockheed Martin collaborate on creating the most recent software updates. As part of the tight collaboration between the United States and the United Kingdom on this programme, British engineers and test pilots have participated in developing the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) since its inception. In 2001, British and American pilots evaluated the prototype together. Italian and British F-35s attained IOC on land in 2018, and British F-35s attained IOC on the water in 2020. However, this knowledge alone is insufficient for constructing a fighter of the next generation from scratch, but it does provide the two nations with a better grasp of what flying a fifth-generation fighter entails on the battlefield. The extra value of combating a fighter of the future generation extends well beyond its remarkable technical skills, like enhanced stealth and excellent manoeuvrability. When it comes to next-generation fighter programmes, sensor fusion is a crucial feature, and the United Kingdom and Italy have the most extensive first-hand knowledge in this field.

The larger European Situation

Several military services will need to modernise their inventories and acquire new weapon systems due to Western countries’ resumption of defence spending growth following decades of underfunding. Several European nations have already selected between the F-35 (Finland, Switzerland, Belgium, Denmark, Poland, Norway, and the Netherlands) and the RAFALE (Croatia and Greece), but export potential inside and beyond Europe are greater than they have ever been. A merging of the two programmes could help to maximise the beneficial outcomes of this window of opportunity by eliminating competition between the most significant European aerospace businesses. The fact that the Italian business Leonardo acquired a 25.1% stake in the German company Hensoldt could be an important factor in lessening rivalry since this would raise the degree of similarity between the radar systems of the two programmes.

A merger would also improve defence collaboration amongst partners, with France and the United Kingdom most likely to benefit. Since the Lancaster House Treaties signing in 2010, France and the United Kingdom have agreed to strengthen their partnership in various fields, including the production of sophisticated, high-value weapons. At the 2018 Sandhurst summit, the two partners underlined their willingness to advance cooperation in light of the positive outcomes, particularly interoperability across armed services. Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapons (FC/ASW) is intended to replace the French SCALP and British STORM SHADOW airborne cruise missiles and the EXOCET and HARPOON maritime missiles.

In addition, they agreed to cooperate and evaluate “coming conclusions prior to making choices on future phases” of developing their respective future combat air systems. The partners have committed to analysing the Future Combat Air Environment, looking at factors such as how manned and unmanned systems may operate together and establishing a high level of interoperability among the most significant European Air Forces, as stated in the final declaration of the 2018 summit.

Cons of the merger

If industrial and military considerations could justify a merger, political and strategic grounds favour keeping the two programmes independent. The British-led and Franco-German FCAS initiatives aim to improve the strategic autonomy of participating nations and keep them competitive in the hunt for warriors of the next generation. However, the United Kingdom strives to strike a balance between capabilities and development time, whilst Germany and France appear to be more concerned with obtaining the greatest technological characteristics feasible than with time constraints. The first effects of these divergent perspectives are now visible: Team TEMPEST has made significant development progress, but the other program’s R&D is lagging. As a consequence of this, it appears unlikely that combining the two projects will make it possible for the many stakeholders to accomplish their aims. This is especially the case when considering the disastrous results of prior cooperation programmes, such as the A400M. The scheduling and technological abilities of the event may be significantly impacted as the number of participants increases. This is because it may become extremely difficult to agree.

A divided Europe

Brexit and European defence are two other crucial considerations. It is well known that France is the member state that pushes the hardest for a stronger EU defence, whilst the United Kingdom has generally rejected stronger cooperative efforts. Unsurprisingly, several examples of collaborative EU defence progress have been made since Brexit. It is too early to judge their true impact, but recent world events have convinced EU nations of the necessity to increase their strategic autonomy via combined defence programmes. Kicking off a new joint programme with a non-EU country would undercut the benefits made so far and will be difficult by the new legal structure in force.

Similarly, the participation of third parties in the programme and the ensuing export policy may impede a merger. TEMPEST members are not forbidden from collaborating with non-European nations. The Japanese government is contemplating selecting BAE Systems over Lockheed Martin to assist Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in developing the F-X next-generation fighter. Japan and the United Kingdom are already cooperating on engine components and sensor technology for their respective aircraft of the next generation. In addition, India could be requested to enter the program as part of a bilateral agreement to boost collaboration, which involves transferring superior technology to produce fighter jets. Given that the FCAS/SCAF programme is planned as a European initiative, that disagreements over know-how and workflow are ongoing, and that Germany has more stringent export regulations than other nations, the participation of third countries constitutes a significant barrier to a merger.

Squabbles continue

The competition for European combat aircraft of the next generation is far from done, and success is not assured. Considering the current status of both programmes, the British FCAS has a greater chance of success. Utilising disruptive technologies to accelerate the various phases of development is likely an effective strategy, but finance will likely be a significant barrier to the program’s completion. Because disagreements amongst the primary contractors are likely to continue for the duration of the programme, the FCAS/SCAF project is currently in a precarious position. Eric Trappier, the CEO of Dassault, claimed in an interview on June 7 at the Paris Air Forum that the FCAS/SCAF may now be delayed by ten years.

Additionally, he reminded that France might identify alternatives, such as extending the modernisation of the RAFALE fleet to extend its operational life. A merging of the two programmes, which may make sense from a purely economic standpoint, will need more political backing and will likely be ineffectual.

Hi everybody,

Two cons are missing here: France wants to develop an Marine version of the FCAS which will be used for its new strike carrier PANG. UK with TEMPEST do not plan such a version. That’s also one of the reason why France and UK looked for different partners in 2017.

Another point is that France wants to keep its airborne nuclear component which have been given up by UK.

So the FCAS program is actually more challenging than the TEMPEST…

I can’t see any mention of the Japanese buy in to the Tempest programme adding significant value, stability and export potential.