Tales of lost treasures have always captured the imagination of humankind since times immemorial. From the legend of El Dorado to the mysterious Nazi gold train in Poland, people have been drawn to the dream of elusive treasures. One such tale is that of the lost treasure of the Indian National Army. Conspiracy theories about Bose’s death and the fate of the treasure abound. Some allege that the plane crash in which Bose carried two leather cases full of gold in Taiwan was not where he met his end. Yet, others believe in his supposed second marriage to a woman of Czech origin, while a trail of information in the Russian files state he was kept prisoner in the Soviet Gulag between 1945 and 1949. The fate of the treasure is equally a mystery. Some indicate that it eventually landed up in the vaults of the National Museum; others say it sits patiently in Swiss vaults. In 1978, when government officials unlocked a time capsule at the National Museum and found among the 14 packages encased in the steel attaché a large collection of gold jewellery, mostly charred. The burnt jewellery revealed in 1978 indicates that a fatal plane crash did occur, but where is the rest of the hoard?

Locked away in the vaults of South Block and protected by the Official Secrets Act for over half a century are revelations of one of India’s earliest scandals. Hundreds of yellowing documents that raise serious suspicions about cash, gold and jewellery that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose collected to finance his armed struggle for Independence were siphoned away. One of the 37 secret ‘Netaji files’ in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) deals with the ‘INA Treasure’. Built over the years with secret reports, letters and telegrams, it reveals a story of rank greed and opportunism which overcame Indian freedom fighters as they looted the treasury of the collapsed Provisional Government of Azad Hind. This suspected loot took place soon after Bose’s alleged demise in a plane crash in 1945. But the startling twist is not about the missing Indian National Army (INA) treasure worth several hundred crores of rupees today. It is that the government of the day knew about it but kept deafening silence.

The Trail of the Hoard

On 29 January 1945, Indian residents of Rangoon(now Yangon), the Japanese-occupied Burma capital, held a grand week-long ceremony. It was the 48th birthday of Netaji. Netaji was weighed against gold, “somewhat to his distaste“, Hugh Toye notes in his biography, “The Springing Tiger: The Indian National Army and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose“. Over Rs 2 crore worth of donations were collected that week, including more than 80 kg of gold from Indians in Rangoon. Netaji had raised the largest war chest by any Indian leader in the 20th century. The significance of this fortune is marked by the way in which it was amassed. Affluent Indians donated tremendous amounts of riches settled in South East Asian countries, all for the cause of azaadi. Women lined up to present their personal jewellery and other valuables. In their minds, the struggle for freedom should not have to be fought with the money offered by the governments of Germany and Japan. The family of Saraswati Rajamani, a former member of the Rani Jhansi Brigade, had donated an entire gold mine in Madurai to the movement.

But by April 1945, all this was to no avail as the Japanese army, and the INA strategically withdrew in the face of a resurgent Allied thrust into Burma. Netaji withdrew to Bangkok on 24 April 1945, carrying with him the treasury of the Provisional Government. There are conflicting accounts on how much of the treasure he took. Dinanath, Chairman of the Azad Hind Bank interrogated by British intelligence soon after the war, said Netaji left with 63.5 kg of gold. On 15 August 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers. The 40,000 strong INA also surrendered to the Allied forces in Burma; their officers were shipped off to the Red Fort to face trial for treason. On 18 August, Netaji, along with his aide Lt Col Habibur Rahman and others, boarded a Japanese bomber in Saigon bound for Manchuria, where he would attempt to enter the Soviet Union. Habibur Rahman recounted the last hours of Netaji before the Shah Nawaz Committee in 1956. Netaji had been injured in the plane crash and died in a Japanese army hospital six hours after the crash. Also destroyed in the aircraft were two leather attachés, each 18 inches long, packed with INA gold. Japanese army men posted at the airbase gathered around 11 kg of the remnants of the treasure, sealed them in a petrol can and transported it to the Imperial Japanese Army Headquarters in Tokyo. A second box held the remains of Netaji’s body that had been cremated in a local crematorium in Taiwan. On 7 September, a Japanese officer, Lieutenant Tatsuo Hayashida, carried Bose’s ashes to Tokyo, and the following morning they were handed to the President of the Tokyo Indian Independence League(IIL), Rama Murti.

Where was the rest of Netaji’s war chest? It is beyond belief that over 63.5 kg of treasure could have turned into an 11 kg lump of charred jewellery. An 18-page secret note, prepared for the government in 1978, quotes Netaji’s personal valet Kundan Singh as saying that the treasure was in “four steel cases, which contained articles of jewellery commonly worn by Indian women, chains of ladies watches, necklaces, bangles, bracelets, earrings, pounds and guineas and some gold wires“. It also included a gold cigarette case gifted to him by Adolf Hitler. These boxes were checked before Netaji departed from Bangkok to Saigon. A leader of the IIL in Bangkok, Pandit Raghunath Sharma, said that Netaji took with him gold and valuables worth over Rs 1 crore. There was clearly much more of the treasure than the two leather suitcases burnt in the aeroplane crash. SA Ayer, a former journalist, turned Publicity Minister in the Azad Hind government, was one man who knew this. Ayer was with Netaji during his last few days. On 22 August 1945, he flew from Saigon to Tokyo and joined M Rama Murti, former President of the IIL in Tokyo, to receive two boxes from the Japanese army.

On 25 August 1946, Lt Colonel John Figgess, a military counterintelligence officer posted in the headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia, submitted a report to his superior Lord Louis Mountbatten. Figgess concluded that Netaji had indeed died in the plane crash in Formosa (now Taiwan). On 4 December 1947, Sir Benegal Rama Rau, the first head of the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo, made a startling allegation. In a letter written to the MEA, Rau alleged that Murti had embezzled the funds and misappropriated the valuables carried by Netaji. The formal reply that the President of the Indian Association in Tokyo got from the mission was that the Indian government could not interest itself in the INA funds.

Bench Marks of the Mystery

The government became interested in the INA treasure only four years later, in May 1951, when diplomat, KK Chettur, headed the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo,as India was yet to establish full-fledged diplomatic relations with Japan. Chettur noted with dismay the return of Ayer. He was now a Director of Publicity with the government of Bombay State. Now, seven years later, Ayer was going back to Tokyo on what he claimed was a holiday but actually with a secret agenda. In a series of cables to the foreign office in New Delhi, Chettur also made the first mention of the phrase “INA treasure“. Ayer told Chettur in Tokyo that he had been entrusted with twin tasks by the government of India – to verify whether the ashes kept in the Renkoji temple were those of Netaji and to retrieve the gold jewellery that had been recovered from the crashed aircraft.

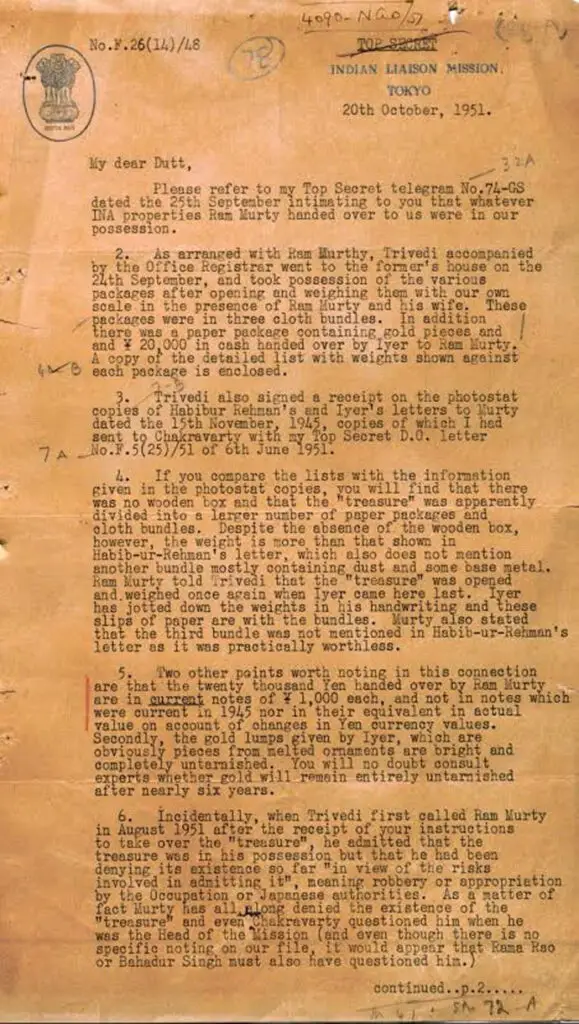

In a secret dispatch to the MEA, Chettur said that local Indians were “seething with anger at the return of Ayer and his association with these two brothers (the Murthys)” because “both Ramamurthy and Ayer had something to do with the mysterious disappearance of the gold and jewellery collected by Netaji“. But Ayer had already pulled a rabbit out of his hat. He informed Chettur that part of the INA treasure had survived and had been in Rama Murti’s custody since 1945. In October 1951, the Indian embassy collected the remnants of the INA treasure from Rama Murti’s residence. Ambassador Chettur still disbelieved the Ayer-Rama Murti story. Chettur believed that Ayer had come to Tokyo to “divide the loot and salve his and Shri Ram Murthy’s conscience by handing over a small quantity to the government, in the hope that by doing so, he would also succeed in drawing a red herring across the trail“.

In one of his final communications to New Delhi on 22 June 1951, Chettur offered to probe the “Netaji collections” disappearance. The first comprehensive warning of foul play in the INA treasure followed just months later. It was a two-page secret note authored by RD Sathe on 1 November 1951. “INA Treasures and their handling by Messrs Iyer and Ramamurthi” summed up the story. All that was left of it was 11 kg of gold and 3 kg of gold mixed with molten iron and 300 grams of gold brought by Ayer from Saigon to Tokyo in 1945. Rama Murti had been questioned several times by Indian officials but had denied the existence of the treasure. Ayer’s activities in Japan were suspicious, Sathe said. Sathe pointed at Ayer’s movements from Saigon to Tokyo, an eyewitness who claimed to have seen the boxes in his room.

Anuj Dhar, the author of India’s Biggest Cover-Up, a book dealing with the mystery surrounding freedom fighter Subhas Chandra Bose, believes that this was “independent India’s first scam“. With the help of confidential documents from the ministry of external affairs, Dhar has concluded that a “Gang of Four” was responsible for the loot. According to his book, Munga Rama Murti of the Indian Independence League, S A Ayer, the Publicity Minister in Bose’s Provisional Government and Colonel John Figges, the Military Attache at the British embassy at Tokyo, appropriated the proceeds from the treasure. Rama Murti and his brother J Murti “bought two sedans and were seen riding about in them, seemingly leading quite a luxurious life” at a time when even the affluent Japanese were reeling under the financial miseries brought about by the World War. Figess had also submitted an official report in 1946 confirming the death of Netaji in the alleged air crash.

Rama Murti’s proximity to British intelligence officer Lt Col Figgess had baffled most Indians in Japan. He was posted at General Douglas MacArthur’s occupation headquarters in Tokyo as a Liasion Officer. What was the glue that held Colonel Figgess and his erstwhile INA foes together? “Suspicion regarding the improper disposal of the treasure is thickened by the comparative affluence in 1946 of Mr Ramamurthy when all other Indian nationals in Tokyo were suffering the greatest hardships. Another fact which suggests that the treasures were improperly disposed of is the sudden blossoming out into an Oriental curio expert of Col Figges, the Military Attaché of the British Mission in Tokyo and the reported invitation extended by the Colonel to Ramamurthy to settle down in UK.” This note was signed by Jawaharlal Nehru on 5 November 1951. “PM has seen this note. This may be placed on the relevant file,” then Foreign Secretary Subimal Dutt signed off on it.

Ayer received a warm welcome by the Prime Minister when he met him in New Delhi on his return from Japan. Conclusive evidence that Netaji had died in the air crash could help silence government critics. This evidence came from Ayer. On 26 September 1951, Nehru wrote to Foreign Secretary Dutt that Ayer had met him with an inquiry report. Ayer, Nehru wrote, “was dead sure that there was no doubt at all about Shri Subhas Chandra Bose’s death on the occasion“.It now turns out that Chettur’s suspicions were correct. Ayer was on a covert mission for the government. In 1952, Nehru quoted from Ayer’s report in Parliament affirming that Netaji had indeed died in an air crash in Taipei. Tracing the antecedents of the people involved in the loot, Dhar, in his book, says that Colonel Figges was “an honoured guest” at the marriage of Murti’s younger brother. Murti’s Japanese wife wore Indian jewellery that some people alleged had come from the INA treasure. In 1952, Rama Murti and his Japanese wife got embroiled in a case of tax evasion and were forced to shift to India. J Murti went on to open a restaurant of Indian cuisine in Tokyo. Figges “is now remembered in the United Kingdom as Sir John Figges, a leading authority on Oriental porcelain“.

The INA treasure, or what was left of it, was secretly brought into India from Japan. It was inspected by Nehru, who called it a “poor show“. There was a brief debate within his Cabinet on what to do with it. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the Education Minister, suggested the gold be given to Netaji’s family. Nehru overruled the suggestion. The jewellery was sealed and consigned to the vaults of the National Museum in Delhi. In 1953, Ayer was appointed Adviser, Integrated Publicity Programme, for Nehru’s Five Year Plan. The extended Bose family, descendants of Netaji’s large family of 13 siblings, refuses to believe there was an air crash.

Consequently, they have neither accepted the treasure nor the ashes. They rebuffed an attempt by the Nehru government to send them the gold in 1953. On 30 December the same year, the government sealed the box and handed it to the museum. The warnings from the Indian mission in Japan continued to pour in. In 1955, AK Dar, the Ambassador in Tokyo, made another explosive accusation. In a four-page secret note sent to South Block, Dar again demanded a public inquiry which would at least determine who the likely culprits were if it would not get back the treasure.

Nehru’s silence on the fate of the INA treasure is baffling, especially since the Shah Nawaz Committee set up by him to probe Netaji’s disappearance in 1956 also recommended an inquiry into its fate. It was impossible to conclude what had happened to the treasure, the Committee noted and called an investigation into all the assets of Netaji’s government.

The revelations within the ‘INA Treasure’ file are a ticking time bomb that has been known to all that matters. In 2006, the government declassified one INA treasure file from the sensitive ‘Not To Go Out’ section of the PMO. File 23 (11)/56-57 now placed in the National Archives is, however, scrubbed of any references to the angry reports from diplomats Chettur, Sathe and Dar. The file only speaks of the 11 kg of gold that survived the air crash, now in the National Museum, then located in the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

Purabi Roy in her book, The Search for Netaji: New Findings, which the Communist government almost completely suppressed in West Bengal at the time, has been looking for answers and faced with a multitude of hurdles, most of which, she believes, have been placed there by those in power. Purabi Roy recalls her meeting with Col Hugh Toye, a British Military Intelligence Department officer during World War II. She got deeply involved with the mystery of the missing INA treasure when she headed an Indian research team, which went to Russia and Britain in the mid1990s to gain access to archived intelligence files that had been made accessible to the public. Since then, Roy has spent the last 18 years digging through hundreds of files in India, Britain, and Russia, trying to determine the fate of Subhas Chandra Bose, the Indian National Army, and their purported wealth. Her quest led her to Toye in 1996. Toye, whose responsibility during the war was to track down and arrest members of the INA, dodged her efforts to meet. Eventually, however, he gave in. Post an amiable lunch; he asked her in earnest about where the INA money was. The question flummoxed Roy. According to reports in the Russian archives, Toye had been present at a landmark meeting in Singapore in 1964, where Nehru, Mountbatten, and the Malayan Governor dealt with the INA wealth that had come into their hands. A frustrated Toye then told her in confidence that he had handed over ₹72,000 crores worth of money to Jawaharlal Nehru and Mountbatten himself, and after that, the trail ran cold.

According to the book Netaji: Rediscovered, by Kanailal Basu, in 2009, the riches came into Hugh Toye’s possession upon the assassination of A Yellapa, the branch manager of the Azad Hind Bank in Taunggyi, in present-day Myanmar, by British forces. The book’s author insists that Yellapa had been carrying ₹7 crore and 170 pounds of gold bars, which amount to a fraction of the fabled ₹72,000-crore figure. In her book, Purabi writes about her meeting with Toye as well as an archived report, which claimed that Jawaharlal Nehru and Mountbatten may have divided the sum between themselves. Toye was questioned by the Mukherjee Commission in early 2000, which is when he laughingly referred to her as “a snake in the basket“. Toye’s claims were never corroborated. Classified papers revealing how the Nehru government ignored warnings from officials in Tokyo between 1947 and 1953 also includes a letter by RD Sathe, then an MEA Under Secretary to PM Jawaharlal Nehru, stating that Bose left a substantial amount of this treasure in Vietnam, which then was stolen off by India’s freedom fighters who were involved in Bose’s INA.

The Shroud of Denials

Two prominent Indians based in Japan who deposed before the one-man inquiry commission headed by Justice GD Khosla in 1971 also claimed the treasure had been embezzled. They told Justice Khosla about the sudden affluence of the Murtis in Japan. One of the witnesses, veteran Tokyo based journalist KV Narain, asserted that Ayer had come to Japan with two suitcases of jewellery which he gave Rama Murti in 1945. In its report of 30 June 1974, the Khosla Commission noted that part of the treasure had been misappropriated by Ram Murti and his brother J Murti. But the Commission could not find proof and felt the quest would not yield anything. SA Ayer’s Mumbai based son, a retired Brigadier, rubbished the speculation that his father had anything to do with the embezzlement of the INA treasure. Netaji’s grand nephew and Trinamool Congress MP Sugata Bose says he is aware of Rama Murti being treated with suspicion by the Shah Nawaz Committee but dismisses reports linking Ayer to the missing treasure as “speculative“. J Murti’s son Anand J Murti, who runs a chain of restaurants in Tokyo, stated that he is baffled by the allegations in the files.

That part of the INA treasure had been secretly transferred to Delhi in a secret operation that was revealed only in the 1970s. In 1978, Subramanian Swamy, then a Janata Party MP, made a sensational public claim that Prime Minister Nehru had embezzled the INA treasure. In a letter written to Prime Minister Morarji Desai, he demanded an inquiry into the disappearance of the treasure and its covert transfer to India. Desai made a statement in Parliament later that year that part of the treasure had indeed been transferred to India. A secret report submitted to Desai’s PMO by the MEA summed up all the facts of the case, beginning from Netaji’s final journey to the arrival of part of the treasure to India. It included the role of Chettur, the whistleblower in the case, and the questionable conduct of Ayer and Rama Murti. The Morarji Desai government, however, did not order an inquiry. The INA treasure case was quickly forgotten. Sadly none of the key players is alive today.

One of the last claimants to the INA treasure died in 2012. Ramalinga Nadar, the son of Rangoon based businessman VK Chelliah Nadar, had petitioned the government for the Rs 42 crore and 2,800 gold coins that his father had deposited in the Azad Hind Bank in Rangoon in 1944. “In 2011, RBI officials told the Nadars they had nothing to do with the INA treasure and treated the matter as closed,” said his son in law KKP Kamaraj.

Postscript

Soon after the formation of the Indian National Army, the British started to feel the heat. The Indians were massively supporting INA, and due to this, the name of Netaji Bose was engraved in each and every Indian’s heart. So after attaining Independence, it would be Netaji who would have been India’s first Prime Minister. Nehru’s dream to become the Prime Minister would have never become a reality if Netaji had been in India. The only way of achieving his aim was by eliminating Netaji from India. As soon as Japan surrendered, he was distraught and lost all hopes. If he had returned then, of course, the British were waiting for doling him a punishment which would have been equivalent to death. Netaji’s bodyguard, Usman Patel, revealed that Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi were planning to hand over Netaji to the British. It is speculated that Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi, Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Maulana Azad had agreed with the British to hand over Netaji to them if in case he returned to India. The question remains as it has for over half a century, whether the nation can handle the withheld truth, when and if revealed.