India achieved its highest annual defence export ambition in 2018-19, with INR 107.45 billion ($1.54 billion) in arms exports and export authorizations. After breaking into the world’s top 25 defence exporters for the first time, India has set an even higher target of INR 300 billion ($5 billion) in defence exports by 2025.

Can India stand among major defence exporters?

What would it take for India to realize its defence export goal? And what has India done to achieve it? The paper examines India’s recent defence export performance and, in so doing, it probes various reform initiatives taken by the Indian government to promote international arms sales. India has a significant domestic arms manufacturing capability that, if utilized properly, has the potential to propel the country as an important player in the global arms bazaar.

India broke into the list of the world’s top 25 defence exporters for the first time in its history and now the country has set its goal even higher. The draft Defence Production and Export Policy, released in August 2020, has set an ambitious target of INR 300 billion ($5 billion) in defence exports by 2025. Can India achieve the target and join the ranks of major arms exporting countries? What would it take for India to realize its ambitious defence export goal? And what has India done to fulfil its ambition?

If anyone asks India what one or two lessons it has learnt from the ongoing Ukraine war, it may spontaneously say—to give more push for self-reliance in all sectors, including the defence field.

Any discussion or debate in the defence sector should be fact-based. If one goes by the reliable facts, it is evident that India is the major importer of defence equipment, arms, and aircraft. At the same time, it’s spending on the defence sector has been increasing in recent years. It could be because of more purchases as well as cost-escalation.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, also known as SIPRI, says India is the largest importer of arms globally, and the biggest seller of weapons to India is Russia. Between 2017 and 2021, the five largest arms importers were India, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Australia, and China. The US tops the list of the biggest exporters globally. It is followed by Russia, France, China, and Germany.

India, which professes peace and bilateral talks in place of conflicts, is way ahead of many other countries when it comes to arms imports. The reasons could be many, including having hostile neighbours like China and Pakistan, besides not being self-reliant. As per the SIPRI report, India and Saudi Arabia accounted for 11% of global arms imports between 2017, and Saudi Arabia’s market share was equal to that of India’s.

It is imperative to examine India’s recent defence export performance and compare it to its ambitious $5 billion targets by 2025.

It is also vital to examine the defence industry and procurement reforms that the Indian government hopes will energize indigenous arms production and, in turn, help realize the government’s export ambitions. India has significant domestic defence research and development (R & D) and manufacturing capabilities, which, if harnessed correctly, could make the country a significant player in the global arms bazaar.

From the flashback of defence

It is difficult to understand the present or future of the Indian defence sector without first understanding its history. India’s extensive reliance on Russia for arms supply dates back more than seven decades.

The Ilyushin IL-14 cargo transport plane is the first Russian plane to land here. It was a two-engine Soviet commercial and military personnel and cargo transport plane. The first IL-14 was a gift from the Soviet Union to the Indian Air Force and was called Meghdoot-1. Many variants were later purchased. The IL-14 service was discontinued in 1979. From 1962 to the present, Russian imports have steadily increased. As a result, Russia’s aircraft legacy in India is extensive.

But the truth is that India never bothered to ask the Soviets or Russians to share their technological know-how. Whether it be the MiG aircraft, guns, submarines, frigates, or Bofors, India did not bother to study and absorb the technology. There was no let-up in the ad hoc selection of equipment and aircraft. That was probably all India could do in the early decades after independence. Forget about designing an aircraft; until the 1990s, the country had not even designed or manufactured a two-or four-wheeler. The colonial rule had taken a toll on India.

The list of missile systems, missile launchers, artillery systems, helicopters, aircraft, ships, submarines, battle tanks, and naval systems of Russia being used by India is far too long. The SIPRI Arms transfer database has put out the list which captures the supply from 1999 to 2021. But once the USSR disintegrated to become Russia, the supply was reduced mainly because of the inability to supply by the new dispensation and also reduced budgetary allocations by the Indian government. But between 2011 and 2021, imports went up by 42% higher than in the previous decade. Between 2017 and 2021, India will be first among all the countries importing Russian arms. India’s share was 27.9%.

The SIPRI Trend Indicator Values (TIVs) indicate that Russia’s exports to India were worth $597 million in 1992, and they touched their peak in 2013 at $3,853 million. And, from 2014 onwards, i.e., when the NDA government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power, the imports declined. In 2019, it was $1,182 million, and in 2020, it was $969 million.

The Congress regime, rightly or wrongly, looked toward Russia for its arms supply, while the BJP has begun giving business to other countries, including the US, France, and Israel, among others. Interestingly, India’s arms imports from France have increased tenfold. But Russia still tops the list of suppliers of the highest number of arms to India. This is even though Russia’s share of arms imports to India fell from 69% in 2012-2017 to 46% in 2017-2021. The IAF is using no less than 410 Russian (including Soviet era) fighters. They are a combination of both imported and licenced-built platforms. All four MiG-21 and MiG-29 variants are dependent on Russian spares and components.

The export of arms has rarely been a focus of domestic arms manufacturers in the past.

The Indian government, for its part, was also hesitant to encourage arms exports, even though it had no compunction about running a huge import bill. However, with the liberalization of the defence industry in 2001 and the entry of the private sector into defence manufacturing, exports have assumed a great deal of importance.

The current government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in particular, has emphasized the importance of indigenous arms production and exports.

Propelled by several reforms aimed at increasing international arms sales, India’s defence exports and export authorizations have risen dramatically in recent years, albeit from a low base.

India’s Defence Exports

| Year | Export authorisations to private companies (INR billion) | Export by DPSU/OFB (INR billion) | SCOMET issued by DGFT (INR billon) | Total Export (INR billion) |

| 2016-2017 | 1.94 | 13.28 | 0 | 15.22 |

| 2017-2018 | 31.63 | 15.19 | 0 | 46.82 |

| 2018-2019 | 98.13 | 9.33 | 0 | 107.46 |

| 2019-2020 | 80.08 | 9.05 | 2.03 | 91.16 |

| 2020-2021 | 72.71 | 9.85 | 1.79 | 84.35 |

| 2021-2022 | 39.25 | 0.99 | 0 | 40.24 |

As shown in Table 1, defence exports and export authorizations have seen a significant jump, with 2018-2019 recording the highest ever international sales. As per the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), India, for the first time, entered the list of top 25 major exporters from 2015 to 2019. Though India’s share constitutes a meagre 0.2% of total global arms exports and the country remains far behind major exporters (such as the US, Russia, France, and the UK), it is nonetheless an achievement for the country, which still continues to live with the uneasy distinction of being one of the largest arms importers in the world.

As per the numbers on Table 1, it is important to note that the total import figures do not always represent India’s final transnational arms deals. Unlike the state-owned realities (DPSUs and the quondam OFB), the government does not provide accurate defence import numbers for the Indian private sector and munition SCOMET specifics, which are classified as defence specifics but whose import authorizations are granted by the DGFT.

Instead, it provides values for import authorization. Given that some import authorizations may not be translated into actual physical exports, the import figures in Table 1 are overstated.

This overestimation is not contradictory; the trend is clearly upward. The number of import authorizations granted by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) also shows an upward trend. Between 2016-2017 and 2019-2020, the number of authorizations for defence imports increased by 215 per cent, from 254 to an estimated 800.

The Indian private sector is driving the increase in India’s defence exports, accounting for 68–98% of total defence exports in these five years. This is a significant accomplishment for this fledgling industry, which was prohibited from producing arms until 2001. Nonetheless, private sector exports are largely limited to corridors, factors, and sub-systems, unlike state-owned realities. They are largely driven by India’s offset policy, which allows foreign arms suppliers to return 30 per cent of the value of large defence contracts to Indian assiduity.

In November 2021, Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL) signed a $ 90 million import order with Airbus for radar warning receivers and bullet approach advising systems, marking a rare big neutralize-driven import order for a public sector reality. The private sector is limited in exporting major details due to its low exposure to defence products, which public-sector firms still dominate. Still, as previously said, the private sector’s fortunes are shifting, with the government allocating a decreasingly larger share of domestic arms production to it.

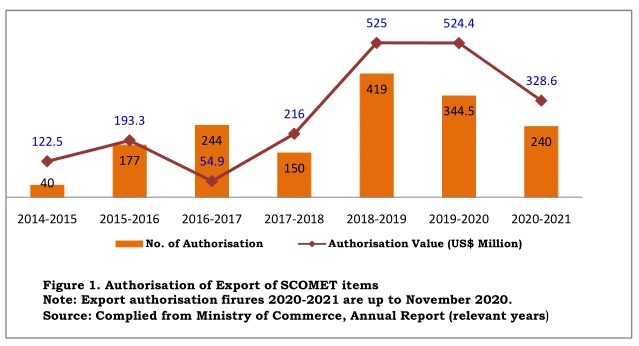

It’s worth noting that while defence exports have risen in recent years, so has India’s assiduity’s import of high-tech items on the SCOMET list. Several defence businesses manufacture these particulars and their exports. As shown in Figure 1, the quantity and value of import authorizations for SCOMET particulars have increased. This demonstrates India’s rising capabilities in the high-tech economy when viewed in conjunction with military exports.

The further analysis

Regarding transnational arms deals, the Indian government has historically been restrained from discovering details of exported particulars and their destinations — the defence frequently being the “strategic perceptivity of the matter” and in the “interest of public security.” The disinclination to furnish details is waning, in line with the government’s bold drive for arms deals. More frequently, the information on India’s arms exports is revealed as part of the administrative question and answer. For case, responding to a question in the Rajya Sabha (the upper house of Parliament) on March 15, 2021, the Minister of State for Defence, Shripad Naik, listed the following particulars which have been either exported or given authorization for import –

Coastal Surveillance System (CSS), Light Weight Torpedoes, Light Weight Torpedo Launcher and corridor, Do- 228 Aircraft, Wheeled Infantry Carrier, Light Specialist Vehicle, Mine Protected Vehicle, Passive Night Sights, Battle Field Surveillance Radar Extended Range, Integrated Anti-Submarine Warfare, Advanced Munitions Simulator, Personal Defensive particulars, 155 mm Artillery Gun Ammunition, Small Arms and Ammunitions, Weapon locating Radars, Identification of Friend or Foe( IFF)- Interrogator etc.

In another reply, the same Minister informed the Parliament that defence particulars were being exported to more than 84 countries, though he didn’t list the names of those countries. Some of the particulars he mentioned in his alternate reply, which didn’t figure in his earlier statement, include tear gas launchers, alarm monitoring and control, night vision monocular and binocular systems, fire control systems, high frequency (HF) radios, littoral surveillance radar, etc.

Though the Minister did not mention the destination of India’s arms exports, the Ministry of Defence, in one of its ad-hoc publications, a Coffee Table Book, has provided some lesser data in the form of item and country-wise shipments in addition to the names of the exporters. Pellet-resistant (bullet-proof) jackets and helmets were the most widely exported items, with 34 countries receiving them, followed by arm factors ( 23 countries). These air platforms are state-owned Hindustan Aeronautics, Ltd (HAL) aircraft currently flying outside of India. India has so far exported coastal command vessels (Mauritius, Sri Lanka, and Seychelles), rapid attack craft (Mauritius), and interceptor boats under the nonmilitary platform order (Mozambique).

Lightweight torpedoes have been exported to a number of countries as part of the murderous arms order. MKU, which specializes in the manufacture of defensive equipment, has the most presence in 36 countries, followed by Indo MIM Pvt Ltd (15 countries).

A key feature of India’s defence exports is that most big items (such as transport aircraft, helicopters, or naval vessels) are exported by the DPSUs and through noncompetitive sales. Orders are obtained from friendly foreign countries because of their strong political ties to India. Among the few export orders won in global competition, HAL’s Dhruv helicopter sales to Ecuador stand out. Bagged in 2008 by beating a rival bid from Elbit of Israel, HAL won the $50.7 million contract for supplying seven helicopters, though the post-delivery experience was marked with bitterness.

Another feature of Indian defence exports is that they are not known to be associated with offsets (or industrial and economic reciprocities), a requirement India demands when purchasing foreign-made items beyond a specific value. A known exception to this private builder is L&T’s export of patrol vehicles to Vietnam, where it was required to transfer “design and technology” for the local construction of seven boats.

It is not now that India is facing Russia’s spare and component shortages. Even back in 2015, the government stated that only 55% of the IAF’s combat fleet was operational because of a spare parts shortage.

India is not only reducing imports from Russia and diverting business to other countries; it is pushing for Atmanirbhar Bharata, meaning indigenous development. The Make In India policy is getting priority in all sectors, including defence equipment manufacturing.

One fine illustration to show the focus is earmarking not less than 68% of the capital budget for 2022-23 for domestic manufacturing industries.

The SIPRI’s trend report points out that India’s total volume of imports has come down by 21% from 2012 to 2016. There could be many reasons for this, but the main reason is working towards indigenous manufacturing of arms, weapons, components, and other related systems.

In addition, India should be tapping the export market. It is far too much to expect India to become self-sufficient in the near future as it has begun the journey in real terms now. Even China imports defence equipment. The wiser approach is to collaborate and produce high-quality products to reduce costs. This is precisely what the present Indian government is promoting.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the Rs 20 lakh crore package on March 12, 2020, to promote the Make in India mission. In other words, the government has made available about 10% of the GDP to meet the goals under the Make in India mission. The defence sector has taken prominence under the mission. The Indian armed forces urgently require financial resources to modernize. Neither making available resources nor a quantum leap in technology can take place overnight. But one can confidently say that India is moving in that direction.

The defence sector has immense potential to offer employment directly and indirectly. In December 2021, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh put the size of India’s defence and aerospace manufacturing sector at Rs 85,000 crore, and the projected growth for the next year was Rs one lakh crore. It is expected to be around Rs five lakh crore by 2047, the year India celebrates 100 years of independence. If the expectations are met, that would be the right way to celebrate the century of freedom — being self-reliant.

In addition, Singh also emphasized that the role of the private sector will be important in the march towards self-reliance. While the private sector contributed Rs 18,000 crore to defence and aerospace manufacturing in 2021, it is expected to reach Rs one lakh crore by 2047. He had given credit to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) for making the defence sector larger. Indeed, private investors have become the game changers in the defence sector.

The contribution of the public sector to the defence sector is estimated at Rs 68,000 crore, while that of the private sector has touched Rs 17,000 crore. All these and more have not happened overnight. An ecosystem that can make the industry grow and sustain itself has been created. Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war have upset the plans, though not detracked them.

The government’s decision, which triggered the efforts or forced them to indigenize, began when the government notified the public in August 2020 of the first “negative indigenization” list, comprising 101 items. The list was later renamed the “positive indigenization list,” and three such lists have been notified so far. In reply to Lok Sabha in March 2022, the Ministry of Defence stated that besides the 209 items of goods and services getting into positive indigenization lists, another such list of a total of 2,851 Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs) had been announced. The import of items listed has been restricted to give impetus to the domestic industry, it stated.

Structural Renovations Triggered

Because, in announcing the indigenization lists, the government looked beyond the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) for the development of the defence field, a well-thought-out process has brought major structural changes in the defence sector. It is well reflected in the 2023 budget, which prioritized the defence sector with a 10% increase in overall allocations. The capital outlay for defence services has increased by 14% to Rs 1.6 lakh crore. The majority of this funding will be used to improve infrastructure.

The much-needed emphasis on research and development is now being given in the private sector. Up to 25% of the defence R & D budget – nearly Rs 53,000 crore – has been set aside for local industry, startups, and academia.

It is to be seen how best private entrepreneurs make the most of the reforms being pushed. For example, the government has increased the domestic industry’s share in the capital procurement budget to 58% from the earlier 68%, taking the procurement budget to Rs 1.24 lakh crore in 2023. This has kept the defence wings on their toes to hunt for local suppliers and send a message to the regular foreign product suppliers that India will slowly reduce imports. Another message is that foreign companies now have immense scope to collaborate with Indian companies for design and technology transfer. The cap on foreign direct investment (FDI) in the defence sector has been increased to 74% through an automatic route to lure foreign companies.

Though there is no leapfrog development, the policy initiative has yielded positive results. For example, in the last three financial years – from 2018 to 2022 – of the total 197 capital acquisition contracts signed, 127 contracts have taken off with Indian vendors for the capital procurement of defence equipment for the armed forces.

The Indian defence industry, till 2001, was confined to the public sector. But it was opened up to 100% for Indian private sector participation. Till March 2022, a total of 568 defence industrial licences to 351 companies have been issued. Of these, 113 companies covering 170 have begun production.

Decentralization power is a welcome step. The DRDO and Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs) have been delegated powers to explore export opportunities and participate in global tenders. This would have been unthinkable a couple of years ago because of the monopoly of the DRDO.

The government understood that the sector would not become self-reliant without innovation and investment. The Innovation for Defence Excellence (iDEX) framework has been launched to promote innovation and technology development in the defence and aerospace sectors in the private sector. Currently, 132 startups have been roped in, and 66 contracts have been inked for prototype development. The iDEX products are gradually gaining approval from the defence wings.

There used to be opaque transparency in the decisions or activities taken up by the defence department or DPSUs earlier. Now, through the SRIJAN portal and its Dashboard, developed by the Department of Defence Production (DDP), Ministry of Defence, one can get information regarding the status of indigenization progress. There is more transparency regarding DPSUS’ activities to make Atmanir Bharata a reality. The portal is a one-stop-shop for the vendors.

While on the ground, many positive developments are taking place. One noticeable thing is that India is confidently talking about its Make In India mission to make the world hear. Mr Narendra Modi, during the sidelines of the Quad meeting in Tokyo in May 2022, extended a strong invitation to American companies to participate in co-development, co-design and co-manufacture under the Make In India and the Atmanir Bharaa programmes under the defence verticals.

The Western media has reported that the Joe Biden government has offered India a $500 million aid package. This is to make India move away from Russia for military arms purchases. However, no official details are available in this regard. It is speculated that the US may offer F-35 stealth fighters or naval ships, mainly to get India out of Russia’s influence in the defence sector and also to ensure India remains in the anti-China alliance. Is this a trap laid by the US or an attempt to network with India to take on China? It is difficult to make an educated guess until the US announces the terms and conditions. Also, the question to ponder is whether accepting such “generosity” by the US is needed when India is keen on getting technology and design transfer from top arms manufacturers.

The need of the hour is to build a modernized military system without relying much on foreign countries. Being branded as an importer, moving towards Make In India and then getting a tag as an exporter is undoubtedly going to be a long journey. But India has to trek that path without giving room for corruption, nepotism, and red-tapism. To do away with a defence shopping list to Russia or America, India must make the sector inclusive of private players. But while doing so, if any corruption makes a company get blacklisted, then India’s intentions and reputation will take a severe beating at the global level.

Defence officials should interact with manufacturing and R & D company players to hear their ideas and get ideas for producing next-generation products. Such interactions are confined to seminars and workshops held for a short duration, but that is insufficient. For various reasons, including producing the best brains—whether in government or outside—the West is far ahead in design, R&D, and manufacturing. India is yet to move in this direction.

Equally Noteworthy

At a glance, the three projects’ lists and aims under the Make in India scheme in the defence sector—–

| Make-I: | government funding of 90% as agreed between the MoD and the vendor. The Centre funded 4 Army projects and 3 IAF projects and manufactured them in collaboration with domestic vendors. Industry funding for prototype development purposes for import substitution No less than 68 projects for the defence forces have received in-principal approval. Basically, they are into manufacturing spare parts, detection systems, light trucks, radars, etc. |

| Make-III: | Indigenously produced weapons systems or equipment developed in collaboration with or using technology transferred from foreign original equipment manufacturers. |

| 2 Defence Corridors: | One each in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu to catalyze indigenous production of defence and aerospace-related items. Encouraging the government and private players to work together to achieve self-sufficiency and fuel the growth of private domestic manufacturers, MSMEs, and startups. |

| Indigenous Products: | Tejas Aircraft – lightweight, multi-role supersonic aircraft; Arjun Tank – 3rd generation battle tank; NETRA-software network used by RAW & IB; Astra – air to air missile; Akash – Surface to Air medium-range missile; Dhanush Artillery Gun system; MRSAM – Medium Range Surface to Air Missile; Agni IV with ring laser gyro & composite rocket motor; BrahMos cruise missile with 70% indigenous content; Pinaka multi-barrel rocket launcher; Helina – anti-tank guided missile, etc. |

| Strategic Partnership (SP) Model: | The SP model was notified in 2017 to encourage long-term partnerships with Indian entities with global original equipment manufacturers. |

| Defence Investor Cell (DIC): | Established in 2018 to provide information and address queries related to investment opportunities, procedures, etc. |

| Inter-Governmental Agreement (IGA): | Cooperation in joint manufacturing of spares, components, aggregates, etc., related to Russian-origin arms. |

What is the potential here?

So far, India’s basket of defence exports has largely been confined to low-value and relatively less technology-intensive parts and components, with a few exports of big platforms-a fact acknowledged by the Indian government. Furthermore, exports constitute a minuscule percentage of India’s defence production; the highest-ever defence exports, achieved in 2018-2019, make up a meagre 13%. This low share does not, however, represent the true potential of the Indian arms industry, which boasts of a sprawling industrial complex, vastly skilled manpower (about 160,000), an annual turnover (of INR 847.6 billion, or $11 billion in 2020–2021), and a diversified range of products that include, inter alia, ballistic and tactical missiles; fighter aircraft; tanks; nuclear and conventional submarines; frontline warships (destroyers, frigates, and corvettes); artillery gun systems; an array of radar and electronic systems; and a large amount of military-grade materials, among others. Some systems have, in fact, attracted interest from many international customers, indicating their confidence in Indian defence items. The Akash surface-to-air missile, developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and manufactured with over 96% indigenization by state-owned entities Bharat Dynamics Ltd (BDL) and Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL), for instance, has nine countries showing interest. The BrahMos supersonic cruise missile, jointly developed with Russia, has six countries evincing interest. Coastal surveillance systems and radars, among others, have an international interest. This is apart from the fact that over 150 items, mostly developed in-house by the DRDO, are available for export. Can India leverage its vast portfolio of indigenous designed and manufactured items to achieve its goal of $5 billion in arms exports?

Pathway to boost the export

To be sure, India has begun to take some serious steps to boost its arms exports. The momentum for this was clearly created by the Modi government, which came to power in 2014. PM Modi, in particular, has taken a keen interest in defence production and has publicly raised the country’s expectations of becoming a major arms manufacturer and exporter. There is also a realization in the government that arms exports, including those in the form of gifts, could go some way towards expanding India’s strategic outreach. The geopolitical intent of arms exports was fully displayed when India decided to gift one of its submarines to Myanmar. The Kilo-class submarine, inducted into Myanmar’s navy in October 2020, was India’s response to China’s increasing forays into a key Southeast Asian country, which New Delhi considers vital for its Act East policy.

Aside from the gift, the government has made its intention to increase exports through various measures and target setting. As a big push for exports, the Modi cabinet in December 2020 approved the export version of the Akash surface-to-air missile for sale to friendly foreign countries. (As per the government, the export version of the missile is’ different ‘from the version deployed with the Indian armed forces.) More significantly, it created a high-level committee consisting of ministers of defence and foreign affairs and the national security advisor to approve the future sale of major systems to various countries, including through government-to-government arrangements.

The government’s exhortation to the industry has led the DRDO, the premier R&D agency responsible for developing frontline defence technologies for the Indian armed forces, for listing over 150 products for export. The list, encompassing nine different categories of items, includes several big-ticket items such as fighter aircraft, airborne early warning and control systems (AEW&C), tanks and other armoured vehicles, towed-artillery gun systems, multi-barrel rocket launch systems, and surface-to-surface, surface-to-air, anti-tank, and cruise missiles, among other items.

For the DPSUs, the mainstay of India’s defence production, the government has given a target of achieving 25% of their respective annual turnover from exports by 2022–2023. Although the target seems ambitious, given that, at present, exports constitute about 4–5% of their turnover, it could nonetheless act as a catalyst for public-sector companies to come out of their usual comfort zone of executing assured orders from the Indian government for the Indian armed forces. With this target in mind, DPSUs have begun factoring exports as part of their business plan and are actively scouting for international markets. Some have already demonstrated early, albeit limited, success, as evidenced by a $21 million export contract signed in November 2021 between missile manufacturer Bharat Dynamics Ltd (BDL) and Airbus Defence and Space for the supply of Counter Measure Dispensing Systems (CMDS).

Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL), India’s most prominent defence company by value, is presently scouting markets in Malaysia, Argentina, and Egypt to export its homegrown Light Combat Aircraft (LCA). In Malaysia, LCA is one of the three contenders (along with the Pakistani-Chinese JF-17 and South Korea’s FA-50) selected from five competing bids for the $900 million deal to supply 18 fighters (with an option of 18 more). Significantly, as part of the bid requirement, HAL is offering 30% offsets – a first in India’s major arms exports. As mentioned earlier, barring one known instance (L & T’s export of patrol vessels to Vietnam), India’s defence exports have been off-the-shelf with no reported industrial participation from the importing countries.

In line with the government’s push for defence exports, the MoD has introduced several policy measures in recent years, beginning with the enunciation of a Strategy for Defence Exports (SDE) in September 2014. The five-page document was the first-ever attempt to institutionalize arms exports by laying down various decision-making structures and schemes to facilitate exports. Following the SDE, the MoD then released a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) to codify the licencing and other requirements to which Indian companies are required to adhere to obtain export authorization. The said SOP has been further streamlined to make it more industry-friendly by simplifying some stringent end-user requirements and inter-governmental consultation processes.

The SDE has been complemented with several other measures that include the creation of an end-to-end online portal to process export authorizations; the setting up of a cell within the MoD to co-ordinate and follow up on export enquires from prospective importers; notification of Open General Export License (OGEL) to facilitate exports of notified items to pre-approved destinations without seeking prior approval; a scheme for prospective exporters to use government testing facilities to test and certify their products; a financial scheme for Indian defence attachés (DAs) to promote arms exports in countries to which they are posted; and the geographical allocation of countries to DSPUs to engage in focussed export promotional activities.

Taking a cue from the US government’s Foreign Military Sales (FMS) programme, through which the American government exports arms to foreign governments and international organizations, India, in August 2019, announced a similar scheme to boost its own defence exports. The Indian scheme, modelled on New Delhi’s concessional Line of Credit (LoC), allows friendly foreign countries to import defence equipment from India at a price (to be suitably modified to accommodate inflation and other mutually-agreed terms) that the Indian government has already paid for its own procurement. Given that India has vast experience in operating LoC in many countries, the scheme has a huge potential for advancing India’s defence exports. Suffice it to say that India’s current portfolio of defence LoCs is worth $1.24 billion, distributed amongst Bangladesh ($500 million), Vietnam ($500 million), Mauritius ($100 million), Seychelles ($100 million), and Uzbekistan ($40 million). It may be noted that some of the LoCs have not worked to the satisfaction of all states. For instance, the $500 million LoC extended to Vietnam in 2016 could not be operationalized, raising questions about Hanoi’s ability to stand up to Beijing, its debt-taking ability, and its willingness to take credit to meet defence needs instead of developmental requirements.

Last but not least, the government has also attempted to plug a gap in technology transfer agreements with foreign vendors that have previously prevented India from exporting arms. A major beginning was made in the contract to acquire 56 Airbus C-295MW transport aircraft. Under the contract terms, TATA, the Indian company responsible for manufacturing 40 aircraft under license, is permitted to export, after completion of its supplies to the Indian Air Force. As India has been manufacturing the bulk of the major platforms in its inventory through the transfer of technology agreements, obtaining export permission could go some distance in realizing India’s export goals. However, this is easier said than done, as foreign manufacturers rarely transfer key technologies. Even if some do so, they often come with a host of restrictions, including on third-party transfers.

Reforms to the defence industry and procurement

If India’s historically low defence exports are partly due to its aversion to arms sales, the weakness and inefficiency in the country’s domestic arms industry and the procurement system are also equally responsible. Since independence, the Indian defence industry has been dominated by public-sector entities consisting of 16 DPSUs and 50-odd laboratories under the DRDO. In addition, there is a small but growing private sector, which entered defence production in 2001. This industry is involved in almost all sectors, ranging from small arms and ammunition to fighter aircraft, shipbuilding, armoured vehicles, and electronic systems and materials. While the DRDO is the principal agency responsible for technology development, the DPSUs and the private sector are mostly captive production agencies. The industry is dominated by state-owned entities for both R&D and production, even though the private sector is making rapid progress in production.

However, public sector-led defence industrialization has not proved effective, with India remaining overwhelmingly dependent on foreign-made arms. The procurement process, codified in the MoD’s Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) – renamed Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) in 2020 – has also reflected this import bias for a long time since its first articulation in the early 1990s.

After the Modi government came to power in 2014, several reform initiatives have been undertaken under Make in India and Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan to revitalize the defence industry and procurement process. Domestic industrial reforms include:

- The launch of two dedicated defence industrial corridors.

- Further liberalization of the cap on foreign direct investment (FDI).

- A host of reforms to revitalize domestic public and private arms manufacturers.

The government has taken a bold step in listing several DPSUs on stock exchanges, besides corporatizing the inefficient ordnance factories, which were earlier functioning as a government arsenal. Public listing and corporatization are intended to improve corporate governance, accountability, and efficiency.

Besides, the public-sector defence manufacturing entities have been given additional tasks to make them more vibrant and strive for greater self-sufficiency. To curb what can be termed as India’s indirect arms import (or import of parts, components, and raw materials by the domestic arms industry for their production purposes), the government has set a target to reduce such imports by INR 150 billion by 2022–2023.

Moreover, state-owned entities have been asked to improve their innovation capacity by focusing on R & D, using emerging technologies, and employing artificial intelligence (AI) in their equipment.

Along with the measures to reform the DPSUs, the government has taken several steps to deepen the private sector’s participation in defence production. Some key reforms include further liberalization of the licencing regime to facilitate easy entry of interested companies to start businesses; levelling the playing field vis-à-vis DPSUs in respect of taxes and duties; and opening up of the government-run trial and testing facilities to the private sector. More importantly, the government has shown a degree of trust in the private sector for the execution of big contracts—a privilege that was largely confined to the public sector in the past.

However, the most significant piece of legislation taken to boost defence production came in the form of an announcement of a negative list (later renamed a positive one). The list, announced in two phases, banned the direct import of more than 200 defence items and, in turn, reserved them for production solely within India. The list assigns an item-specific timeline (of up to 2025) beyond which direct imports are banned.

Consisting of products ranging from arms and ammunition to missiles, fighter aircraft, and submarines, the list, finalized by the newly created Department of Military Affairs (DMA), is anything but a wish list. It reflects the work already being done by domestic players and was prepared after extensive consultation with all the stakeholders, including the users. In other words, there is a reasonable degree of confidence that the Indian industry will be able to manufacture the notified items to the satisfaction of the user services.

Apropos procurement, the government’s reform measures are aimed at providing a conducive atmosphere for Indian companies, particularly the private sector, to play an increasingly larger role in supplying defence needs. A key step in this regard is streamlining procurement categories (under which acquisition contracts are signed either with Indian or foreign entities) to facilitate the Indian industry’s participation in tenders. Furthermore, the indigenous content (IC) requirement for the participation of Indian companies has been increased from 30% earlier to at least 50% in a move to deepen the indigenization process.

To support this higher IC goal, the DAP-2020 also provides numerous other enabling provisions, including incentives for greater use of indigenous materials and software in items being procured from both Indian and foreign vendors; and a set of procedures to encourage domestic industry, including startups and small and medium enterprises (SMEs), to undertake prototyping which could be considered for procurement.

From an export point of view, the changes made in the DAP-2020s offset guidelines are particularly noticeable. In a major overhaul of the guidelines since their first articulation in 2005, the DAP reduced the multiplier from one to 0.5 on parts and components whilst retaining the multiplier of one on the export of complete eligible products. With this disincentive on parts and components, the government hopes that foreign contractors will be compelled to buy complete products and help promote India as a major exporter of arms. Though the impact would only be seen when contracts are signed as per the new provision, it is nonetheless likely to have a significant impact on India’s existing exports, especially those by the private sector, which is at the forefront of India’s defence exports.

Challenges at the doorstep

Though India has made a modest start in its recent defence export endeavours, sustaining it over the long term will not be an easy task. Exporting parts, components, and low-value, low-tech items is one thing; exporting high-value lethal equipment is altogether different. So far, India’s major exports are to countries with low paying capacity and with which it has strong political ties. Besides, barring a few orders, most of the major items are through noncompetitive arrangements.

The greatest challenge India will face in achieving its ambitious target is competition from established players such as the US, Russia, France, the UK, and Israel and emerging players like Turkey and South Korea. In such a scenario, the best chance for India to realize its immediate goal of defence exports is to push some of its most successful products (such as LCA, Akash, and BrahMos) to countries which have shown interest. This would require the Indian government and arms exporters to pursue these countries, with possible support through the LoC, to achieve early successes and, more importantly, build a brand image to sustain exports in the future.

However, much of the responsibility for creating a brand image in the near-to medium-term would fall on the state-owned DPSUs. If for nothing else, these entities are the biggest players in India’s defence industry and are engaged in producing almost all the big-ticket weapon systems for the Indian armed forces. Without the export of such major systems, it is unlikely that India could achieve its export goals and aspire to become a payer of any significance in the global arms bazaar. However, if the past is of any indication, such expectations from the DPSUs are ambitious. Historically, supported by orders from the Indian government, public-sector entities have avoided exploring international markets. Whenever some ventured into the global marketplace, it has not helped the Indian image much. HAL, India’s premier aircraft industry, had a major dent in its image in Ecuador when the latter grounded Dhruv helicopters after a few crashes, even though pilot error and lack of maintenance were the reasons for these crashes. It is therefore vital for Indian exporters to look at training and post-delivery maintenance as an integral part of export contracts to build a credible image in the highly competitive international arms market.

A key challenge to realizing India’s defence exports is India’s political, diplomatic, and bureaucratic inertia. Even though the 2014 Strategy of Defence Exports talks of government support to industry in its export ventures, not much has been seen on the ground in crucial times. For instance, the Indian government’s role in Garden Reach Shipbuilders and Engineers Ltd.’s (GRSE) bid to bag a $319 million export order to supply two light frigates to the Philippines was left much to desire. Even though the state-owned entity was technically compliant and the lowest bidder, it lost out based on the inadequate financial capability to execute the contract. As a government-owned entity with a sizable order book (INR 257 billion in 2020–2021), the Indian government could have provided a sovereign guarantee to Manila, allowing the company to win the contract.

In the medium term, a challenge to sustaining defence exports could come from the changes in the offset guidelines. By reducing the multiplier on the export of parts and components, the MoD risks losing export opportunities, especially from the private sector, which has been the key driver behind India’s defence exports in the past five years. The MoD has to evaluate its current approach if the changes are good enough to promote the export of major systems, as envisaged in the revised offset guidelines, failing which a mid-course correction would be called for to keep the current favourable export momentum.

In the medium to long term, sustaining large exports will largely depend on India’s ability to acquire arms from the domestic industry. As enunciated in the positive list and the project portfolios of the DRDO, India has a huge pipeline of weapons programmes for the domestic industry. If the Indian government acquires these weapons in a time-bound manner, the industry will not only create the capacity and capability to produce them but will also create opportunities to export them. However, indigenous procurement in the past has been marred by undue delays. The MoD has taken certain steps toward compressing the procurement time to the point of issuing tenders. But it has to work on the crucial stages of evaluation and contract negotiations, which are prone to undue delays, to speed up procurement and create space for export.

Last but not least, a challenge to India’s sustained exports, especially of big items, is likely due to the lack of capacity to enforce export compliance. At present, India’s ability to ensure end-user compliance is weak, which, unless addressed, runs the risk of diversion of arms to inimical forces. This outcome could hamper India’s strategic and commercial interests and prevent the government from authorizing such exports due to such fears.

Just the beginning

India’s recent success in defence export is indeed impressive, given the country’s historical aversion to arms export and the inward-looking approach of state-owned entities. However, sustaining exports to achieve an ambitious $5 billion export sales goal would require India to move from its current approach of exporting mostly parts, components, and sub-systems to major platforms and weapon systems. Only through the export of major systems like aircraft, missile systems, and the like can India achieve its export objectives. Though numerous challenges face India’s further progress in becoming a major arms exporter, one thing is certain: the country has the necessary capability and a basket of indigenous products that could be harnessed to realize the country’s export goals.