The Philippines has completed a deal to acquire three BrahMos ground-based missile systems from India for nearly $375 million to boost its Navy, Defense Minister Delfin Lorenzana said on 15th January.

“Recently, I signed a notice of acceptance of the terms of the contract for the acquisition of coastal anti-ship missiles for the Philippine Navy. As agreed with the Government of India, it includes the supply of three systems, training of operators and operational personnel, as well as the necessary integrated logistics support (ILS) package,” wrote the minister on Facebook.

He said that the project was ‘conceptualised’ back in 2017; in 2020, it was approved by President Rodrigo Duterte.

India has not announced the delivery dates so far, but the Philippines expects the delivery in six months.

Speaking to a T.V. Channel, ANC News, the Philippines Armed Forces Spox, Col. Ramon Zagala said, “Those aggressive countries cannot enter into our territory and attack us. This deterrent weapon is part of our credible minimum defense … it will affect their tactical situation in the area … these are meant for defense and never meant to be an offensive weapon.” He also mentioned the missile as a ‘strategic weapon’ in the hands of the Philippines forces.

The Brahmos missile to be delivered to the Philippines Navy is of 290 km range. The Navy is buying three batteries of Brahmos, and the Army intends to buy two batteries in future. Each battery includes two launchers, a radar and a command and control centre. The quantity of missiles is not yet known.

The Philippines is the third South East Asian country to have an ‘over the horizon supersonic anti ship’ capability after Vietnam with Bastion-P and Indonesia with Yakhont.

Why does Philipines require Brahmos missiles?

Rommel Ong, a retired admiral who served as deputy commander of the Philippine Navy until 2019, is quoted by the media saying the missiles are intended in part to counter China’s dispute with the Philippines over land and fishing grounds in the South China Sea. The admiral termed it as an “asymmetric response that does not require large resources.”

China has bolstered its military forces in the region, including building artificial islands and placing weapons on them. This led to incidents. In November, for example, Chinese coast guard vessels fired hoses at Philippine boats carrying supplies for their sailors stationed on the disputed shoal.

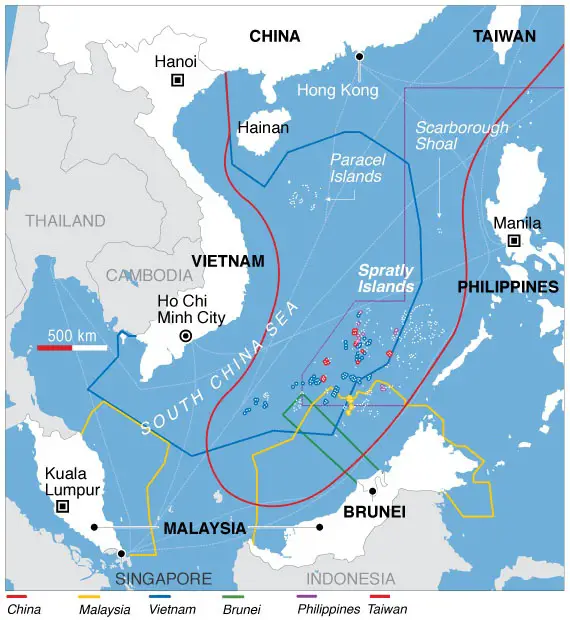

The Philippines is buying the version of Brahmos, which provides for the placement of launchers on the coast. Its range – 290 km – is sufficient to cover part of the disputed water areas, which are also claimed by Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei.

Under Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, relations between the island nation and China have warmed. But Beijing’s claims to the South China Sea, through which more than $3.4 trillion worth of cargo is transported annually, have not been softened. In 2016, an international arbitration ruled that China’s claims were not legally substantiated.

“I don’t see the point in mincing words here–India’s gov’t has made a spectacular breakthrough with the impending delivery of BrahMos AShMs to the Philippine Army, who have now formed a coastal defense unit that will operate the missile. The BrahMos sale is also a clear signal to China that ASEAN member states won’t accept its nonsensical foreign policy of annexing distant waters and imposing control over these,” says Miguel Miranda, formerly a regional Defense reporter and an author of military history books, from the Philippines.

(Also read – Chinese Coast Guard ships use water cannons on Philippine ship in the South China Sea)

“However, we must be realistic about these missiles. Only a small batch is being ordered for either one or two batteries. They are for deterrence purposes. Their intended use is for discouraging the Chinese Navy and coast guard from massing inside territorial waters. The Philippine military has no plans to fight China in the West Philippine Sea even if its personnel are getting harassed and surrounded by Chinese vessels year in and year out. I must admit it’s all a bit too little/too late since China’s naval power is now stretching beyond the “first island chain”, and there are other ways for Beijing to manipulate the Philippines’ leadership besides coercion.

The Philippines has tried to be friendly with China before engaging in an expensive arms race. But since China does not feel any threat to its current behaviour, it is unlikely to come to the diplomatic table.

“It doesn’t help that for six years, the Duterte administration (2016-2022) have bent over backwards to appease China and never released funds for acquisitions that might threaten the Chinese presence in the Spratlys,” says Miguel.

The Philippines didn’t modernise its armed forces in the hope China would be considerate. The Philippines’ military hardware includes World War II ships and helicopters used by the United States during the Vietnam War.

“The only way the Philippines enhanced its surveillance and detection resources is through direct material assistance from Japan and the USA. Until now, the Philippine military doesn’t possess any modern air defenses, nor is there adequate radar coverage for most of the country. The Philippine Air Force is in the middle of its own modernisation and can’t actively protect its territorial expanse. As for the future of the India-Philippines relationship, this is up to New Delhi. As far as Manila is concerned, the problem with China can’t be settled by force. As far as Washington, DC is concerned, access to bases and shared facilities in the Philippines will be very welcome although not prioritised–they’ve learned from Duterte’s perfidy. If India can’t be the all-weather friend the Philippines needs, Japan is too eager to step in if the Chinese ease their grip on the next head of state, ” said Miguel.

How does the Philippines Navy plan to deploy the Brahmos Missile?

The nine dash line, by which China claims its territorial rights, passes through the Philippines too. Despite the International Court of Arbitration ruling or China-Asean code of conduct agreement or Limits in the Seas reports by the U.S. State Department, China has militarised the South China Sea. Parts of artificial islands built by China fall into the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ) of the Philippines. They have been militarised with a large paramilitary, Navy, missiles and other equipment.

Spox Col. Ramon refers to Brahmos as a coastal defense against large ship targets in defense. Metaphorically speaking, the Philippines is threatening a $100 million ship with a $1 million missile. This also means China can continue using it’s Marine Militia and Coast Goard to harass Philipino vessels. But it prevents China from escalating it with its military in case of a reaction from the Philippines against its militias or Coast Guard. The presence of Brahmos can also stop the Chinese from building a military facility near the Philippines. Overall, it prevents the Chinese Navy from operating close to the Philippines. The modernisation of the Philipines armed forces is expected to dissuade coercion by the Chinese and bring them to negotiating table.

Brahmos missile range covers 290 kilometres of the 370 km (200 nautical miles) from the shores of the Philippines, which it considers as its EEZ.