The Indo-Pak War of 1965 holds a unique place in South Asian military history. Overshadowed by the trauma of 1962 against China and the apparent victory of 1971, the 1965 conflict remains a study of bravery, misjudgment, and especially, the steadfast resilience and strengthening of the soldiers’ national will. Lt Gen Vinod Bhatia, PVSM, AVSM, SM (Retd), former Director General Military Operations, called it “The War of Redemption”.

A seminar jointly organised by the Chintan Research Foundation (CRF) and Valley of Words (VoW), led by Lt Gen (Dr) PJS Pannu, PVSM, AVSM, VSM (Retd), with support from Mr. Shishir Priyadarshi, President of CRF, and Mr. Sanjeev Chopra, Festival Director of VoW, aimed to revisit this war with rare candour.

The day-long event was addressed by distinguished veterans and thought leaders, notably Lt Gen Kamal Davar, PVSM, AVSM, Retd, of the 7th Light Cavalry, and Maj Billie Bedi, VrC, of The Scinde Horse (former head of the Aviation Research Centre and founding Director General of the National Technical Research Organisation, NTRO). Both, alongside the late Air Marshal Asthana, belong to the 23rd course of the National Defence Academy (NDA), an exceptional cohort that contributed to India’s leadership in the Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA), NTRO, and the Strategic Forces Command (SFC), as well as the key recommendations of the Kargil Review Committee Report.

The seminar not only honoured the sacrifices of 1965 but also revealed forgotten episodes, overlooked tactical decisions, and the strategic contexts that influenced the war. These lessons are crucial for understanding our military history and developing future strategies.

The 7th Light Cavalry and the Spirit of Defiance

In 1965, the 7th Light Cavalry was converting to PT-76 tanks. According to Army Headquarters’ policy, the unit was not expected to be battle-ready. However, the commanding officer, Colonel Dalip Jind, showed remarkable determination. He persuaded higher authorities to let his regiment march to the concentration area with the available rolling stock, continuing training en route.

This act of defiance epitomised the ethos of the Armoured Corps: to never let institutional inertia override operational readiness. It also highlighted the vital role of leadership in shaping the course of the war. Lt Gen Kamal Davar, then a young officer in his twenties with barely three years of service, would carry this ethos into battle.

Maj Billie Bedi, of the Scinde Horse, a young and spirited individual, was pulled out of the prestigious Gunnery Instructors’ course at the Armoured Corps Centre and School (ACC&S) at his request. This was after he personally petitioned the Commandant, ACC&S, to allow him to rejoin his regiment in combat.

Both the young officers were injured while leading their tank troops against a well-entrenched enemy in coordinated defences.

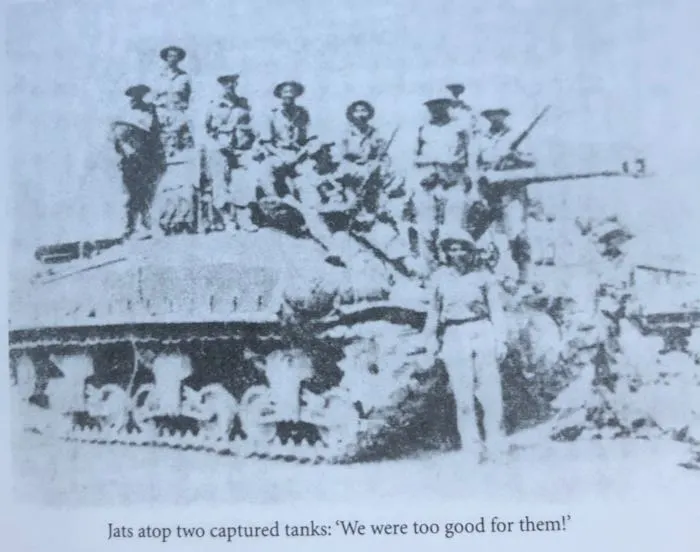

The episode revealed a stark truth: wars are not always won by armies that are fully equipped and prepared, but by soldiers and leaders who refuse to bow to circumstances. Whether on land or air, the Indian man behind the machine was demonstrated as India created a Patton Nagar with 103 Patton Tanks.

Geopolitical Backdrop: Perceptions of Weakness and Miscalculation

The perception of a weakened India significantly influenced Pakistan’s decision to start the conflict in 1965.

The 1962 debacle against China left scars on the Indian military and political psyche.

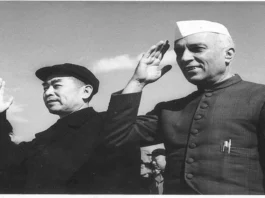

The death of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1964, followed by the appointment of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, created an impression of leadership flux.

During this interregnum, a man of few words, returning from a Non-Aligned Summit, reportedly conveyed to Field Marshal Ayub Khan in Rawalpindi that peaceful coexistence with India was desirable. Pakistan, however, chose aggression over accommodation.

Another key factor was the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy in November 1963. Kennedy had promised to supply ten Indian Army divisions after the 1962 war to bolster India’s defences against China; his commitment concerned Ayub Khan, who saw it as shifting the balance of power. However, when Lyndon B. Johnson took office, U.S. priorities changed. Focused on Vietnam and cautious about alienating Pakistan, a vital Cold War ally in SEATO and CENTO, Johnson quietly delayed the promised arms support to India.

This lack of external support to India emboldened Ayub, who was keen on importing the latest weapons from the US. Ayub was convinced that the superiority of their weapons would probably have him having dinner at the Red Fort in Delhi within 24 hours.

However, the volte face and the Indian Army allowed Shastri to quip, We saved Ayub the travel to Delhi, we can have dinner together at Lahore.

Lal Bahadur Shastri may have been short in height and had a quiet demeanour. Still, he stood ten feet tall when his political directive to the Indian Defence Forces was clear, which enabled the Indian Military to achieve what it did.

Convinced that India remained militarily vulnerable and seeking to strengthen his hold after rigging elections against Fatima Jinnah, Ayub launched a series of operations starting on 1 January 1965. These included probes in Kutch, infiltration under Operation Gibraltar, and the offensive move of Operation Grand Slam. The gamble was intended both to exploit India’s perceived weaknesses and to rally Pakistan behind his leadership.

Indian Armour and Air Power: Numbers and Limitations

At the cusp of 1965, the balance of armour and air power was stark: –

- Pakistan possessed 15 armoured regiments, bolstered by M-48 Patton tanks courtesy of its SEATO and CENTO alignments. It also had advanced aircraft such as F-86 Sabres and F-104 Starfighters.

- India, by contrast, fielded 17 regiments. Its inventory included Stuart and Sherman tanks, AMX-13s, PT-76s, and four Centurion regiments. The Indian Air Force relied on Hunters and the nimble Gnats.

- When Pakistan commenced operations in the Rann of Kutch, its armour manoeuvred with agility, exposing India’s underdeveloped road infrastructure and lack of availability of armour along the border.

- The bigger issue that surfaced was not about numerical deficit but about institutional bias. The Indian Army’s emphasis on the Himalayan border and dismissive remarks by the then Chief of Army Staff at Armoured Corps Centre and & School that “the days of armour are numbered” highlighted a dangerous underestimation of the importance of mechanised forces in plains warfare.

Since then, many a time has the death knell of Armour been called out, including the Ukraine–Russia conflict and the recent OP SINDOOR.

Political Undercurrents in Pakistan

The war also coincided with political turmoil in Pakistan. Fatima Jinnah, sister of Pakistan’s founder, contested the 1965 presidential elections against Ayub Khan. Although she had clearly won the popular vote, the military regime manipulated the election, giving Ayub a fraudulent victory by a margin of 10,000 votes.

Facing a legitimacy crisis, Ayub resorted to external conflict to strengthen his power. The promise of quick gains in Kashmir was presented as a route to national glory, concealing internal divisions.

Thus, Pakistan’s military adventurism was as much about strengthening Ayub’s domestic political position as it was about changing the regional balance.

The Course of Battle: From Punjab to Hajipir

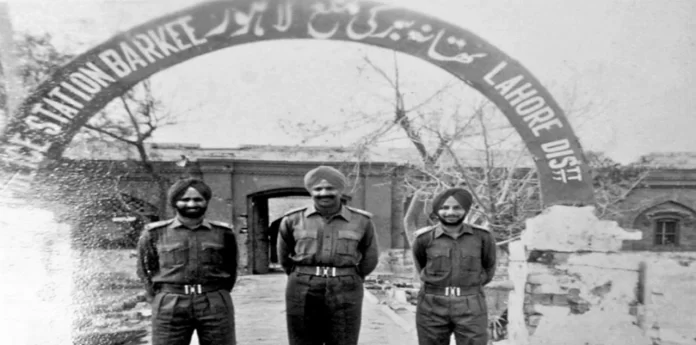

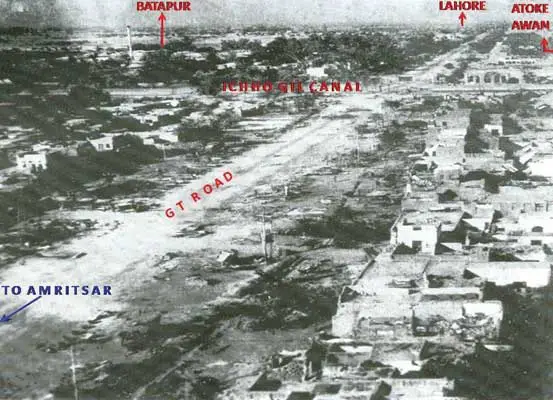

India responded decisively once provoked. On the night of 6/7 September 1965, formations crossed into Pakistani Punjab. 3 JAT, 15 Dogra, and 13 Punjab, supported by the Scinde Horse, advanced to the outskirts of Lahore (Bata Nagar), breaching the formidable Ichhogil Canal.

The 3rd Battalion of the Jat Regiment (3 JAT), under the unwavering command of Lt Col Desmond Hayde, with Capt Baldev Raj Varma as his adjutant, demonstrated extraordinary gallantry in the capture of Dograi. They not only seized the position once but twice, each time against heavily fortified Pakistani resistance. The assaults incurred a high toll, with significant casualties, including the grievous wounding of Capt Baldev Raj Varma, who survived, continued his career with distinction, and retired as Maj Gen Baldev Raj Varma, AVSM.

3 JAT feat at Dograi remains legendary in the annals of the Indian Army. Despite being outnumbered and fighting without adequate replenishment, 3 JAT embodied the highest traditions of courage, resilience, and determination. The eventual recapture of Dograi on the night of 22/23 September stood as a symbol of Indian resolve and an emphatic response to Pakistan’s boast of martial superiority.

Simultaneously, in the high Himalayas, Indian troops captured the Hajipir Pass and Point 13260 in Leh, both strategically valuable. Tragically, these gains were returned during post-war negotiations, reflecting political compulsions rather than military logic.

The human toll of the 1965 war was significant for both sides.

The Indian Army lost about 2862 soldiers killed in action, with around 8000 wounded and nearly 2000 taken prisoner. The Pakistan Army’s losses were higher, with estimates indicating 3800–4000 killed, 8000–9000 wounded, and approximately 2400 prisoners of war held by India.

While Pakistan’s official figures acknowledged only about 1800 killed, neutral assessments from the United States, Britain, and other observers confirm considerably higher losses.

These figures highlight the intensity of the 22-day conflict, during which neither side achieved a decisive breakthrough. Still, both paid a heavy price in blood before the United Nations ceasefire and the Soviet-brokered Tashkent Agreement of January 1966.

Battle of Doagrai – A snapshot of Awards and Casualties

7th Light Cavalry

Casualties

- Killed in Action -Officers -3ffrs, JCO -1, OR – 6

The Scinde Horse.

Casualties

- The Scinde Horse suffered 21 battle casualties, which included both killed and wounded.

Awards

- Vr C – 01, several Sena Medals and commendation cards to officers, JCOs, and men.

3 JAT

Awards

- MVC -03. Vr C -04, SM -07, Mention in Dispatches -12

Casualties

- Killed in Action – Officers -05 JCO-01 OR 82

- Wounded – Officers -09, JCOs – 08 OR -214

13 PUNJAB

Casualties

- Killed in Action – 27

- Wounded – 70

15 DOGRA

Awards

- VrC – 02, COAS Commendation Card – 03

Casualties

- Killed in Action – Officers – 03, JCOs – 02, OR – 58

- Wounded – Offrs – 08, JCOs -12, OR- 205

Field Marshals and the Pakistani Psyche

Over the last six decades, Pakistan’s military elite has consistently positioned itself as the saviour of the nation: Field Marshal Ayub Khan initiated the misadventure of 1965. Gen Yahya Khan presided over the disastrous 1971 war. Gen Zia-ul-Haq entrenched military rule under an Islamist veneer. Gen Pervez Musharraf launched the ill-conceived Kargil conflict.

Today, Gen Asim Munir continues to cast the Pakistan Army as the sole custodian of national interest.

This narrative maintains the Pakistani Army’s dominance over the civilian government. The Pakistani military remains perhaps the only army in the world that owns and governs a country, rather than serving it.

India–Pakistan as Nuclear Rivals

The nuclearisation of South Asia further complicates the landscape. India and Pakistan are often called “nuclear flashpoints,” yet the global discourse rarely applies similar terms to India and China despite their equally hostile disputes and comparable arsenals.

This selective framing exposes geopolitical biases, often exploited by Pakistan to sustain international relevance.

Strategic and Tactical Lessons

The 1965 war, revisited through the voices of veterans like Lt Gen Kamal Davar and Maj Billie Bedi, offers enduring lessons: –

- Operational Readiness over Bureaucratic Caution

- The insistence of Col Jind and the youthful determination of his officers underscore the need to prioritise initiative and adaptability over rigid policy.

- Infrastructure is Strategy

- Pakistan’s ability to exploit developed border roads highlighted the strategic importance of infrastructure. India must never neglect its border connectivity again, a lesson still pertinent in the context of Ladakh and Arunachal.

- Armour and Air Power Matter. Dismissive attitudes toward mechanised forces nearly cost India dearly. Modern wars reaffirm that combined arms, integrating armour, artillery, air power, and logistics, remain the cornerstone of battlefield success.

- Political-Military Synchronisation. Victories at Dograi, Hajipir, and Point 13260, relinquished under political pressure, demonstrate the dangers of a disconnect between battlefield gains and diplomatic negotiations. Military success must inform political strategy, not be bartered away.

- Understanding the Adversary’s Psyche. The Pakistani Army thrives on projecting India as the existential enemy. Recognising this pathology is critical to shaping India’s military, diplomatic, and informational responses.

Over the past six decades, a discernible pattern has defined Pakistan’s approach to conflict with India. Time and again, Islamabad has relied on non-state actors and irregulars to make limited incursions, with the deliberate aim of internationalising the dispute and inviting third-party intervention in its favour. From 1948 through 1999, this strategy was repeatedly employed—and repeatedly thwarted. The 1965 war ended with Russian mediation at Tashkent, while subsequent crises in 1987, 1999, and even up to 2025 saw U.S. involvement to defuse tensions, each time under the looming shadow of nuclear escalation. The pattern remains clear: Pakistan manufactures crises to draw in global powers, while India has consistently worked to resist external interference and maintain the primacy of bilateral resolution.

In the ongoing Operation Sindoor, the Government of India has taken a clear stance: non-state actors and irregulars hired by the Pakistan military will be considered as part of the Pakistani state itself. Any such provocation will prompt a complete and proportional response, leaving Pakistan no room to hide behind proxies while denouncing responsibility.

Deterrence Messaging Must Be Unambiguous. India’s defence forces cannot afford to speak in the language of “restraint” alone. It must follow the dictum, “In God we trust, the rest we monitor.”

India’s adversaries must hear a single, unwavering message: provocation will be met with a disproportionate response.

Broader Reflections

The seminar organised by Lt Gen (Dr) PJS Pannu, with intellectual input from Mr. Shishir Priyadarshi and Mr. Sanjeev Chopra, was more than just a celebration. It also served as a collective reminder that history should be examined critically, not just honoured.

The stories of Gen Davar, Maj Bedi, Lt Col Desmond Hayde, and Maj Gen Baldev Raj Varma reminded the audience that courage, initiative, and professionalism can change the course of war, even when institutions falter.

Equally, the recollection of missteps, including underdeveloped infrastructure, underestimation of armour, and premature relinquishment of territorial gains, underscored the importance of learning from history.

Conclusion

The Indo-Pak War of 1965 was not a decisive victory for either side. Yet for India, it was a crucible that restored confidence shattered in 1962. It proved that Pakistan’s myths of martial superiority were hollow. It revealed the vulnerabilities of relying too heavily on alliances and foreign weaponry.

Most importantly, it forced India to introspect on modernising its forces, building its infrastructure, and integrating political and military strategies.

Today, as India faces persistent challenges from both Pakistan and China, the lessons of 1965 echo with renewed urgency. Our armed forces must remain decisive, technologically advanced, and operationally ready. Our political leadership must synchronise battlefield gains with diplomatic posture.

Our national message must be unambiguous: if provoked, India will not hesitate to impose costs that cannot be borne.

History is not a static record; it is a teacher. The commemoration of 1965, led by stalwarts like Lt Gen Kamal Davar and Maj Billie Bedi, Lt Col Desmond Hayde, and Maj Gen Baldev Raj Varma, is a reminder that the past speaks to the present and prepares us for the future.