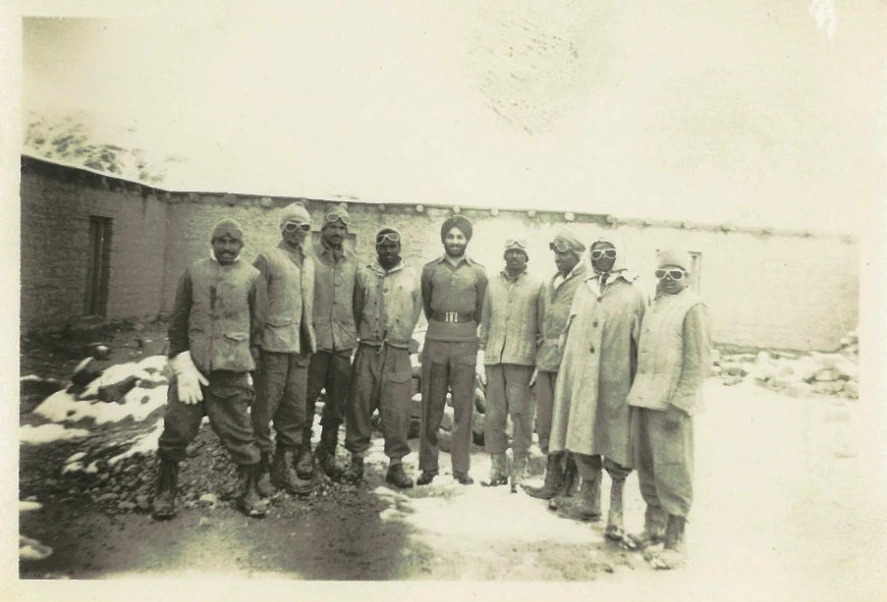

My first posting, in early 1961, was to 372 Field Company, located at Cannanoor (now Kannur), in Kerala—a wonderful location by the beach. Within two weeks my platoon was nominated as the advance party for the move to Ladakh. I was a complete greenhorn then and went to my 2ic, Havaldar Abdullah for advice. He assured me there was nothing to worry about, he would look after it all. We were to report to the OC transit camp at Pathankot for further instructions. He directed us to go to Nagrota, just north of Jammu. This was the staging area for 641 Corps Troops Engineers (CTE), which we were to become a part of. The next move was to Srinagar, in preparation for the final move to Chushul.

Those days we did not have staging camps for acclimatization and had little knowledge of High-Altitude effects. Our flight to Chushul was in late April, on a Fairchild Packet aircraft, it was quite a flight. We were seated on folding seats on the sides of the fuselage, which was not pressurized, only the flight deck was. The rest of us had to manage with an oxygen cylinder that we passed around. Some of us did not do well when we climbed to altitudes of 20-21,000 feet, to navigate through high mountain passes.

This narrative is essentially about our activities during 1962 when we operated as an independent platoon under 641 CTE. It covers the withdrawal from Demchok on the night of 27/28 Oct 1962.

In most actions, many defenders did not survive, nor write about it. I fall into the latter category. This is the reason why very little information is available about these skirmishes/conflicts. Two official records on the withdrawal from Demchok just say:

- “The troops in conjunction with those on the High Ground were asked to carry out a withdrawal by night 27/28 Oct. The withdrawal was successful and completed by 2330 hours. The defenders successfully evaded the Chinese roadblock under the cover of darkness and arrived in Koyul in good spirits”.

- “Indian troops were able to withdraw during the Night of 27/28 Oct to Koyul and Dungti in fairly good order”.

This narrative elaborates on what really happened on night 27/28 Oct 1962, during the withdrawal from Demchok.

I am stepping out of my tent into a bright sunlit day. It is early May 1962, the temperature gauge is showing –20 degrees Celsius. It is not calibrated to go below that reading, so we are never sure of what the actual outside temperature really is, or how low it gets at nighttime. Because of the severe working conditions in winter, the working season for Chushul, at an altitude just below 15000 ft, was between the months of Apr and Oct.

During the working season of 1961, the platoon was mostly deployed with 372 Field Company on the resurfacing of Chushul airfield. We also commenced construction of mud brick huts for 1/8 GR Bn HQ. Small detachments were sent to posts at Sirijap, Gurung, and Maggar hills to build bunkers and strengthen their defenses.

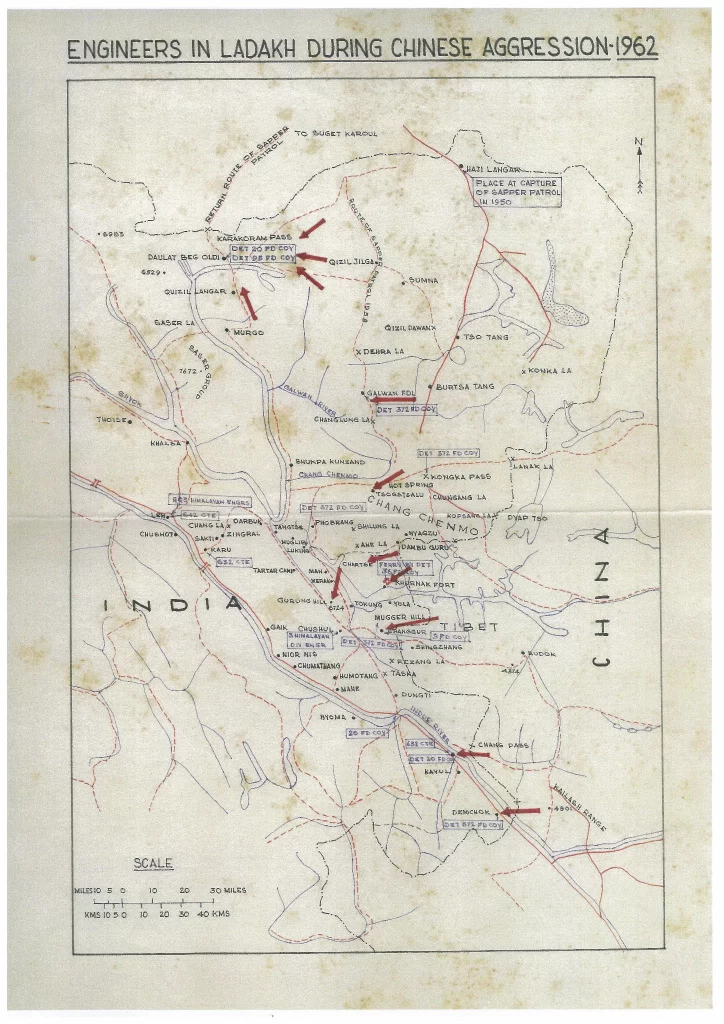

For the 1962 season, 372 Field Company was sent to Leh under 642 CTE, for speeding up the development of Leh airfield. I was returned to Chushul under 641 CTE, as an independent platoon commander. Other units of 641 CTE at that time were 9 and 36 Field Companies.

Those days the Ladakh Sector came under 114 Infantry Brigade (Bde), located at Leh. The Bde commander was Brig T N Raina, who later became the Army Chief. Initially, it consisted of three battalions:

• 14 Ladakh Scouts – responsible for the area north of Hot Springs post towards Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO).

• 1/8 GR Battalion – covering the area between Hot Springs to Rezang La, just south of Chushul. The CO was – Lt Col Hari Chand.

• 7 Ladakh Scouts – covering the area south of Rezang La to Demchok. CO was – Lt Col Banon, seconded from the Dogra Regiment.

5 Jat and 13 Kumaon – joined the Bde later.

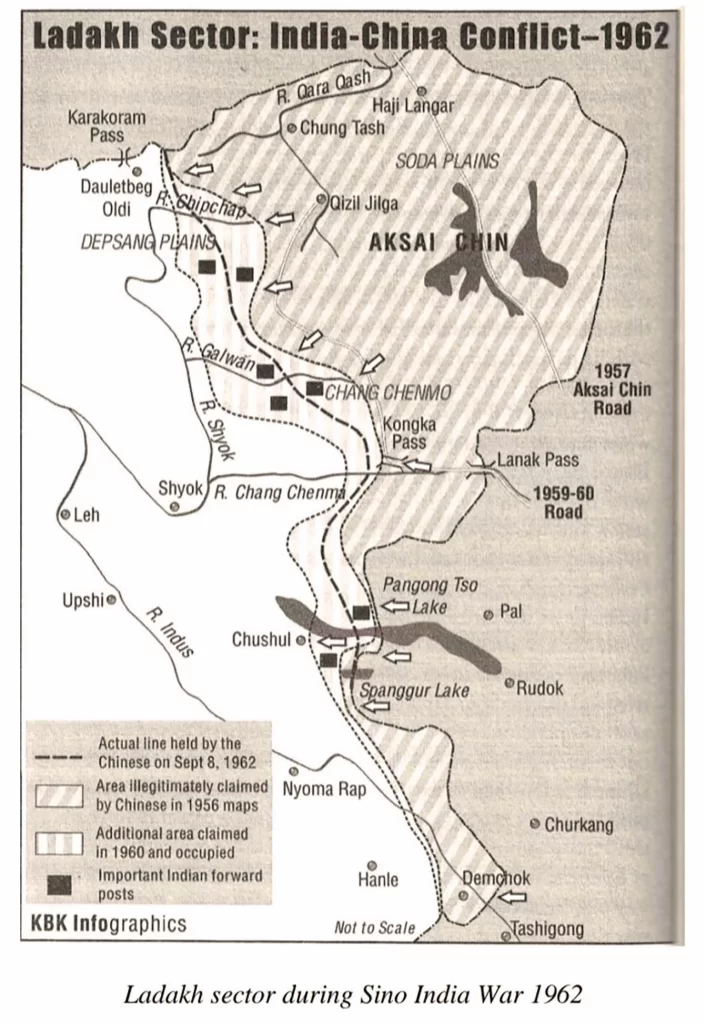

The above deployment came about as part of the Forward Policy adopted by India, in response to the Chinese entering Ladakh in the late 1950s. The Chinese had constructed Road G219 connecting Xinjiang to Western Tibet. This was a strategic road for the Chinese military and economic interests in the region. Around 160 Km of this road passed through the Indian territory of Aksai Chin of Ladakh, refer to Map 1.

During 1962, the platoon was heavily engaged in assisting posts of 1/8 GR along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the construction of bunkers and strengthening their defenses. It was a fortunate stroke of luck that the adjutant of 1/8 GR was a schoolmate of mine from Bishop Cotton School in Shimla, making our cooperation much easier. These posts were at the following locations.

• Galwan, the northernmost post just south of DBO, is only reachable by helicopter.

• Hot Springs, further South of Galwan and North of Phobrang.

• Sirijap 1 & 2, on the northern banks of Pangong Tso. There was a Chinese post in between the two. We would pass this post in our storm boats on the way to our Sirijap posts. On our outward journey, we would see Chinese troops lined up for morning tea. One sentry would walk along the banks till we had left their area. This was the time we would wave out to each other.

• A post each at Gurung and Maggar hills, overlooking Chushul airfield to the West and Spangur Gap to the East across the LAC. These two posts were at mountain tops of about 17,000ft high, where troops had to be turned around every three months because of the high altitude.

All our posts were isolated and located individually along the LAC, with no mutual support capabilities. This was done primarily to protect Indian territorial sovereignty and deny further encroachments by

China. Map 2 shows the deployment of the platoon, as 372 Field Company detachments, in this sector.

Pangong Tso is a long beautiful “L” shaped salt-water lake extending from India to China. It has a myriad of shades reflecting the variety of colors from mountainside rocks and the sky. It freezes in winter when vehicles can drive over it.

Sometime around Jun/Jul 1962 the post at Galwan was being threatened by the Chinese and there was an urgent need to strengthen its defenses. This is when I was told to send a small detachment to the post to speed up the construction of their defensive positions. I discussed this with Nb Sub Ghanapathy, the platoon 2ic, asking him to recommend suitable names. He immediately volunteered to go himself and selected a multi-skilled sapper to take with him. I remember when seeing them off on the helicopter from Chushul airfield, a thought crossed my mind – wondering if I would see them again. I never did, as the post was later completely wiped out. There were no survivors.

As the year went on, the resurfacing of Chushul Airfield was proceeding well, enabling AN-2 aircraft to operate from it. Taking away the dependence on smaller aircraft such as the Fairchild Packet. Work on the construction of bunkers and defenses on 1/8 GR posts was also proceeding as planned.

Move to Demchok

During this period a platoon of 20 Field Company was located at Koyul in support of 7 Ladakh Scouts. All seemed well, till one day we received the sad news that Lt Mascharenas, the platoon commander, had passed away suffering from Pulmonary Edema. I was called up and given the additional responsibility of relieving them and taking over the support of 7 Ladakh Scouts.

I went down to Koyul and met the CO of 7 Ladakh Scouts, to introduce myself and say that we would now be their sapper support platoon. The tasks he outlined for us were:

- Operating a Class 9 ferry service across the Indus River at Dungti.

- Maintenance work to keep Fukche airstrip, near Koyul, fully operational. This was a small airstrip that could only be used by smaller aircraft like the Dakota.

- Providing frontline support to the company post in the Demchok area. This was the southernmost post in Ladakh, where the Indus River flows from Tibet.

- Constructing a causeway across the Chading nullah, connecting the high ground forward defenses of Demchok with their firm base.

Incidentally, I had done a reconnaissance (recce) of this area during the winter of 1961- 62, to check options for the construction of a crossing across it. I chose to go on this recce by forgoing my annual leave that winter. There is a hot spring further upstream, which flows into this nullah. In winter the water from the hot spring starts to freeze as it flows down towards the Indus. It keeps expanding in size as more and more hot spring water flows down and starts to freeze, making it impossible to construct a permanent crossing here. Local troops had built a little hut nearby with a bathing tank, with both streams of hot and cold water flowing in. It was a wonderful relaxing spa in the high-altitude wilderness, which I had enjoyed more than once.

Unbelievable as it may appear, a single sapper platoon was then spread out along the LAC with detachments from the Galwan post in the North to Demchok in the South, spread out over a distance of around 200 km.

After the briefing with the CO, I set out on a recce of the new area. It emerged that at Demchok the priority was minelaying in front of the defences and creating a causeway across the Chading nullah.

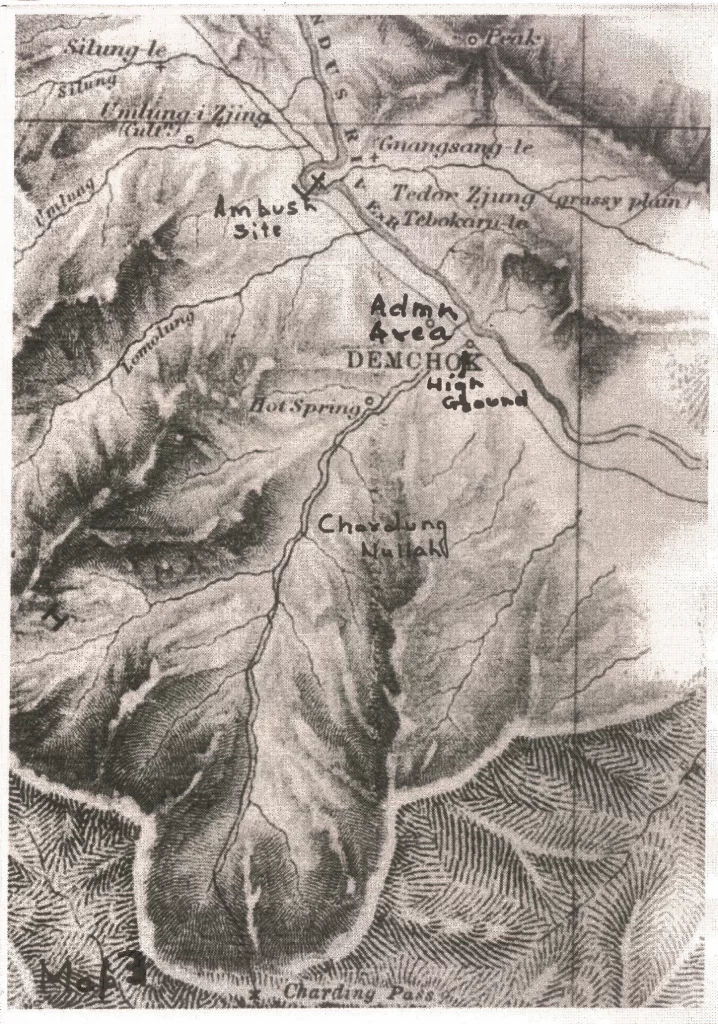

The Demchok defenses consisted of the following three distinct posts, refer to Map 3:

- The high ground on the southern side of the Chading nullah- the main post of the company, commanded by Maj Sharma.

- A small detachment facing the opening from the Chading nullah.

- The administrative base on the northern side of the Chading Nullah and west of the Indus River.

This is where the track from Bn HQ at Koyul ends.

I soon realized that additional troops had to be mustered for the timely completion of these urgent tasks. So, I proposed to the CO 7 Ladakh Scouts that he place his pioneer platoon under me, to assist in the minelaying activities. I planned to move our platoon base from Chushul to the Dungti ferry site, with the main team coming down to Demchok. I went back to Chushul to brief Commander 641 CTE of these plans.

We started the move out of Chushul in Sep/Oct 1962. This is the time when the Indus River starts to freeze. This process leads to a period when the ferry service cannot operate anymore. Crossings then are best done on foot early in the mornings, when the ice thickness is the best for crossing over. Later in the day, the water starts to come above the ice layer, making the crossing more dangerous.

The move from Chushul to Dungti was done in stages, bringing small groups across in early morning trips.

On our last trip, we got a bit delayed, and the water level had risen above the ice by the time we returned. Since I had some experience in finding safe routes across the ice, I asked the men to follow me. I was just about 15 meters short of reaching the other bank when the ice below me cracked and I fell into the Indus River. Luckily, this was a shallow stretch, and I only went down to my waist. Wondered what might have been the outcome had the ice cracked in deeper waters?! On reaching the other bank I dragged myself out of the river and ran towards the huts about 100 meters away. By the time I got there, my trousers were completely frozen. We all managed to get across safely.

Demchok Roadblock/Ambush

At Demchok, I started the recce of the forward positions for the minefield layout. During this time the pioneer platoon of 7 Ladakh scouts had arrived, and we commenced their minelaying training. This was no easy task, as we were dealing with the very sensitive anti-personnel mine – Schumine – Mark 1 & 2, which sets off with just a 15 lb pressure. All this training and preparation took us about two weeks. The proposed layout of the minefield in front of the defenses was finally approved by the company commander. During this period the bulldozer driver had also arrived and commenced work on the Chading nullah crossing.

I was under no doubt that all our activities in the area had not gone unnoticed by the Chinese post facing us. Each morning before going into the forward defences, I would meet the company commander to brief him on our proposed activities for the day. On the day we were to start minelaying, I met him as usual to check whether he had noticed any activity in front of the defenses. He said all was normal and we could proceed.

The next morning, we set out for Demchok, leaving behind a small detachment at Dungti to look after the Class 9 ferry site and operate as our administrative base. Further down the track, we came across a bulldozer working on the maintenance/improvement of the Dungti – Koyul track. This track runs along the western side of the Indus River. I stopped and spoke to the operator, who said he was from Project Beacon, which was a part of the Border Roads Organisation (BRO). BRO was a separate task force that did not come under the Army. He was operating on his own without any supervisor on site. Considering how he could help us with the crossing over the Chading nullah, I asked the operator if he could come down to Demchok for a few days for an urgent task, and he agreed. I think this decision was made easier because both of us wore turbans!

After about half an hour of minelaying activity, we suddenly came under heavy Chinese mortar and small arms fire. The attack found both the minelaying party and the causeway construction party coming under fire. The causeway party, which was behind the company’s defenses, was able to withdraw back to the base easily. The minelaying party was caught between the crossfire of the Chinese and our own defenses. Luckily the area was a sort of riverbed with large boulders strewn about. This provided us with some cover, enabling us to get back to our defenses safely. I got into the bunker of the company commander to assess the situation. We decided that my group would go back to the administrative area across the Chading nullah and await further orders.

In response to the Chinese attack, Bn HQ sent down reinforcements to strengthen the troops at Demchok. By late afternoon we got the sad news that the reinforcements had been blocked from reaching Demchok by the Chinese, who had set up a roadblock cutting off Demchok from the North. There were very few survivors. Sometime later in the day, we received withdrawal orders from Bn HQ.

The sector commander, Maj Sharma, and I were at different posts, so we fixed a rendezvous (RV) at the base camp where we would meet to continue the withdrawal. It was hoped that we would be able to build up sufficient strength to overcome the Chinese roadblock. Withdrawal was to commence at 1800 hrs and some troops from other posts kept arriving at the RV during the day, but most of the force did not. By then we had also lost radio contact with other posts. Two possibilities then occurred to me, either the company had been massacred by the Chinese or they had been compelled to follow a cross-country route over the mountains to avoid the Chinese roadblock.

By now our party at the base camp consisted of 1 RMO (Captain Ghosh), I JCO (Sange) with a platoon strength of Ladakh Scouts, and two section strength of Sappers with me. We also had around 7 vehicles, not counting the bulldozer. It is relevant to mention here, that I was not from the same unit as most of the troops there. Excluding the RMO who was a Captain, I Just happened to be the senior most officer there and had to take charge. I discussed the situation with JCO Sange, and we decided not to wait any longer and to make our own withdrawal plans. Options discussed were:

- Do we withdraw or stay back? Staying back meant becoming POWs.

- Do we get back by road or take another path? Another path over the mountains meant leaving behind the sick and wounded, as they would not be able to walk. This was not an acceptable option.

- To withdraw by road, we had to go through the Chinese roadblock with the hope of getting through under cover of darkness.

We took the difficult decision to withdraw by road and rush through the Chinese roadblock. Bn HQ was informed accordingly. We commenced our withdrawal around 2000 hrs. The plan was:

- Remove all non-essential personnel back onto the Koyul track. Destruction of all equipment and stores that could not be taken back.

- Placing enough kerosine oil in the built-up area to burn contents when the need arose.

- JCO Sange to commence moving back with all vehicles and men and stop short of the roadblock site. The vehicles were to move back as quietly as possible and not to switch on any lights.

- I, with an LMG group, would stay back as the rear party to allow the others to make a clean break. This also gave us time to try disabling the bulldozer, which had to be left behind.

In the time I then had to myself, one thought crossed my mind – this might be the end for us. I was too young, just 22, and had hardly seen any life.

After giving the group sufficient lead time, I got into my jeep with the small group left behind and started back on the track to Koyul. We soon caught up with the main group. In the dim light, we could see the silhouette of the earlier ambushed Shaktiman vehicles.

The ambush site was at a place where the track moved away from the Indus River, creating a sort of open area covered by the mounds in front and on the western side. For an ideal site for an ambush, refer to Map 3.

We lined up with the one Shaktiman in front followed by other vehicles, and the rear being brought up by a Shaktiman with an LMG facing the rear to take on any spoiling Chinese assault from that side. My jeep with JCO Sange would be in the lead. Final instructions to the troops were to just drive through and open fire in all directions as soon as we came under fire.

I got into my jeep with JCO Sange, and we started moving forward. When we came closer to the roadblock site the Chinese fired “Verey” light pistols and the whole place lit up like daylight. All hell broke loose with intense firing from all directions. In this rush, the JCO’s LMG, which was leaning a bit outside our jeep, smashed into a passing telephone post and fell away. We just pressed on. Unbelievably, we got through the ambush and stopped a safe distance away from the site to check our convoy. While the whole of the sapper team had come through safely, some casualties were suffered by the Ladakh Scouts.

We reached Koyul around midnight on the night of 27/28 Oct and I reported to the Duty Officer. He asked me where we had come from? When I said Demchok, he was completely shocked and just could not believe it. They did not expect us to make it through the Chinese roadblock/ambush. From there, I left Koyul and continued with my sapper team to our Dungti base. The platoon was separated from its parent unit – 372 Field Company which was at Leh, and from the 641 CTE group at Chushul, about 125 Km to the North. Consequently, they were not made aware of our activities at that stage.

On reflection later, while considering what we had been through, two thoughts occurred to me.

- Our direct assault on the Chinese ambush party must have completely surprised and shocked them. They perhaps thought we were a much larger force than we were. From aggressors, they became defenders, more concerned for their own safety.

- The difficulty of aiming fire at moving targets in the darkness of the night worked in our favor.

Quite significantly, I believe that this incident was perhaps the only action in the 1962 conflict, where Indian troops were not just holding a defensive position, but instead went on the offensive. We rushed through the Chinese roadblock/ambush site successfully. That too led by a sapper officer.

Later, we got the news that the main group from Demchok High Ground chose the mountainous cross-country route avoiding the Chinese roadblock. This took them about 3/4 days to get back to Koyul, with many arriving with frostbite and other injuries.

Considerable changes had taken place at Chushul since we had left. 114 Inf Bde moved from Leh to Chushul and additional troops including 13 Kumaon, a detachment of AMX-13 Tanks and some artillery units had also been brought in to strengthen defenses. We were told to remain at Dungti where defences had also been strengthened with the arrival of units from 70 Inf Bde.

The heavy battle of Chushul took place on 18–19 Nov. Our troops held back the Chinese. A ceasefire was declared on 21 Nov.

Later Years

I managed to get leave on Dec 62 and on my return went to 641 CTE at Chushul. It was only then I got to relate the details of the withdrawal from Demchok and the break-through of the Chinese roadblock /ambush site.

Soon, after that I started getting correspondence from the Chief Engineer XV Corps, asking for more details about the withdrawal, in an effort for a gallantry award citation. This process continued for over a year or so, but nothing came of it. Later, I was informed that all that could be done now was to make an entry in my Record of Service, which was done.

I also started receiving correspondence from Project Beacon of Border Roads, calling for an explanation as to why I took their bulldozer to Demchok without any permission. This correspondence also carried on for quite a while before it died down.

In 1978, I had the good fortune to get command of the 9 Engr Regiment, the most decorated regiment in the Corps of Engineers. I took premature retirement in 1982.