On the eve of Army Day, after a silence that had lasted nearly four decades, the Government of India took a bold and deeply meaningful step. By publicly acknowledging the valour, sacrifice, and service of the Indian Peace Keeping Force, it offered something long overdue to Veterans, Veer Naris, and next of kin: closure with dignity. The timing was deliberate, the message unmistakable. It was not merely an act of political symbolism but one of moral responsibility.

Addressing veterans at the Maneckshaw Centre, the Raksha Mantri formally acknowledged the courage and sacrifice of those who served with the IPKF in Sri Lanka, emphasising the importance of their contributions in fostering respect and appreciation among the audience.

Operation Pawan was never a simple military deployment. It was a convergence of diplomacy, coercion, optimism, misjudgement, courage, and cost. To inform future strategies, we must explicitly identify lessons learned, such as the importance of realistic threat assessment and clear exit strategies, to ensure these insights guide operational frameworks.

A Flawed India–Sri Lanka Agreement: Why Was India Taken by Surprise?

The oft-repeated claim that India was “taken by surprise” in Sri Lanka deserves scrutiny. A sudden intelligence failure did not blindside India. It was undone by strategic self-deception.

The political DNA of the India–Sri Lanka Agreement itself contained the seeds of failure. The agreement was born of compulsion, not consensus. President J. R. Jayewardene signed it under intense internal pressure from Sinhala nationalist forces. The LTTE accepted it under coercion, not conviction. Any political settlement that lacks legitimacy among its principal stakeholders, especially the primary armed non-state actor, is structurally fragile. This was neither unforeseeable nor unforeseen.

Political optimism replaced military realism. India’s leadership believed that its regional stature, diplomatic weight, and moral authority would compel compliance. The LTTE was misread as a political movement with negotiable aims, capable of being guided into constitutional processes. In reality, it was an absolutist insurgent organisation, forged through violence, sustained by fear, and structured for total control over territory and population. This was not a misunderstanding of intent; it was a refusal to accept it.

Intelligence was present but filtered. Both RAW and military intelligence issued warnings about the LTTE’s intentions and capabilities. However, assessments that challenged the political narrative of “peacekeeping” were softened or sidelined. What was missing was not information but an integrated politico-military assessment presented to the Cabinet Committee on Security, complete with worst-case scenarios and clear risk articulation.

Force structuring followed the agreement rather than the threat. The IPKF was inducted with limited Rules of Engagement, light equipment, and a peacekeeping mindset. When the LTTE predictably reneged, India was forced into reactive escalation, inducting additional formations incrementally and without operational coherence.

Most critically, India entered without an exit-linked strategy. There was no shared understanding of what success or failure would look like in military terms. Objectives remained political abstractions, detached from operational realities.

India was surprised not because the situation changed overnight, but because it chose not to accept a fundamental truth: coercive peace enforcement against a determined non-state actor is, by another name, war, underscoring the need for future strategic readiness.

The ‘Capture’ of Jaffna: A Moribund Strategy Against an Unconventional Foe

The battles for Jaffna have often been mischaracterised as failures of execution. In truth, they reflected a profound doctrinal mismatch, specifically, the reliance on conventional war paradigms against an unconventional enemy. Recognising this helps strategists develop adaptable doctrines for future complex environments.

Conventional war paradigms shaped the Indian Army in 1987. The 1965 and 1971 wars remained the dominant institutional reference points. While counter-insurgency experience existed, it was largely rural and domestic, not urban-littoral warfare against an ethno-nationalist insurgency embedded within a dense civilian population.

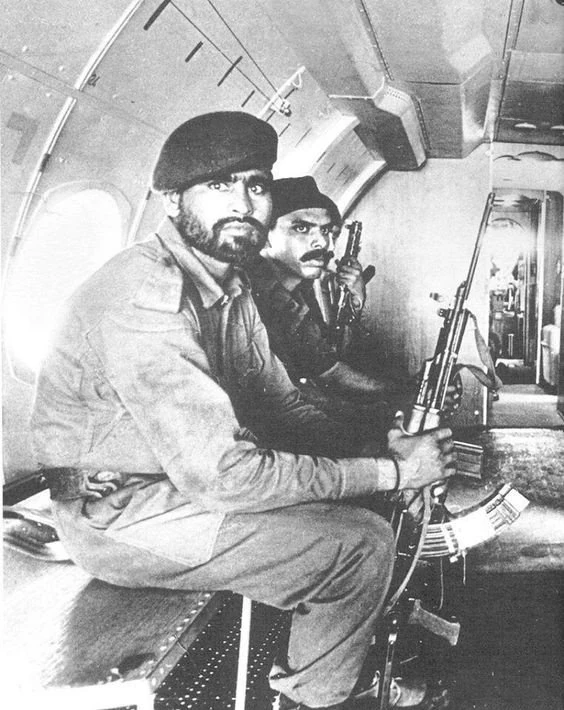

The LTTE was dangerously mischaracterised. It was treated as a lightly armed guerrilla force, yet it had a hybrid structure: cell-based urban fighters, sea-borne logistics, prepared defensive positions, and absolute civilian control. Jaffna was not merely terrain to be seized. It was a political capital, psychologically and socially inseparable from its population.

Time pressure distorted planning. Political urgency to demonstrate control over Jaffna led to rapid operational launches without adequate terrain familiarisation, intelligence preparation, or cultural understanding. Units were inducted piecemeal into an environment they had neither trained for nor studied in depth.

Force application became excessive and inefficient. Division-sized formations, armour, artillery, and special forces were employed in ways suited to set-piece battles. The result was high casualties, civilian suffering, and damage to infrastructure. In a peace enforcement mission, this was strategically counterproductive.

The most damaging factor was the absence of a unified civil-military campaign design. Success was measured by kilometres gained rather than by legitimacy secured. This underscores the need for integrated planning that aligns political objectives with military operations to enhance future operational effectiveness and legitimacy.

The lesson is stark. Conventional superiority cannot compensate for conceptual inferiority. Against an unconventional adversary, doctrine decides outcomes long before numbers do.

Fallacies About Operation Pawan: Success, Stay, and Sudden Withdrawal

Operation Pawan is often judged through a distorted lens, with political objectives retroactively conflated with military outcomes.

By December 1988, India had achieved the original political objectives of the India–Sri Lanka Agreement. The secession of Tamil Eelam had been prevented, and Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity had been preserved. India’s regional primacy had been unmistakably demonstrated.

Yet the mission did not end. Why?

Objectives evolved mid-campaign without formal revision. Once engaged in combat with the LTTE, India became enmeshed in Sri Lanka’s internal power struggles. The IPKF transitioned from peacekeeping to peace enforcement and, eventually, to de facto counterinsurgency. This shift occurred without a renewed political mandate or strategic recalibration.

Several factors prolonged the stay. There was fear of a strategic vacuum. A hasty withdrawal risked LTTE resurgence and damage to Indian credibility. Colombo had grown dependent on the IPKF to balance internal threats. Bureaucratic inertia also played a role, as institutions tend to justify their continuation once committed.

Why then the withdrawal in 1989?

The answer lies in the political transition in New Delhi. The new government reassessed costs against interests. Casualties were rising. Tamil public opinion had turned hostile. There was no strategic dividend commensurate with the effort. Relations with Colombo were deteriorating rather than stabilising.

Withdrawal was not a defeat. It was a strategic disengagement when costs exceeded benefits. The fundamental fallacy is treating Operation Pawan as a binary success or failure. It was a limited political success, an operationally costly campaign, and a strategic cautionary tale.

De-induction of the IPKF: Lessons from a Quiet Strategic Success

If there is one phase of Operation Pawan that deserves more study, it is the withdrawal.

The de-induction of the IPKF succeeded precisely because it avoided drama. Political clarity preceded military action. Withdrawal was negotiated with Colombo, ensuring host-nation cooperation and preventing miscalculation.

The process was phased and layered. Rear areas were stabilised first. Combat units were thinned gradually. Logistics were meticulously sequenced. No artificial prestige deadlines were imposed.

Command discipline was exemplary. Despite provocations by the LTTE, formations exercised restraint, preventing a spiral of violence during disengagement. This restraint saved lives and dignity.

Information control was equally important. There was no iconic “last helicopter out” imagery. By denying adversaries a propaganda moment, the withdrawal denied them a psychological victory.

History offers sharp contrasts. Vietnam and Afghanistan failed not only because of battlefield outcomes but also because of chaotic withdrawals. The IPKF avoided this fate through a methodical disengagement.

The lessons are enduring. Always plan the exit at the entry. Withdrawal is not the end of war; it is a phase of it. Political legitimacy matters most during disengagement. Tactical restraint preserves strategic dignity.

Structuring for Future Out-of-Area Operations

Operation Pawan conclusively demonstrated that out-of-area operations cannot be improvised. They demand purpose-built structures and integrated thinking.

India requires standing, integrated OOA task forces. These should be brigade-level, modular, and capable of operations across air, sea, and land. They must possess organic intelligence, electronic warfare capabilities, UAVs, and civil affairs units.

Doctrine must evolve to address hybrid warfare. Future missions will be peace enforcement, not peacekeeping. Urban, littoral, and information-centric operations will dominate.

Leadership development is critical. A specialised cadre of officers trained in politico-military operations is essential. Cultural literacy, language skills, and negotiation ability must be treated as operational requirements, not optional extras.

Diplomatic and economic enmeshment is not optional. Future missions must embed diplomatic advisors for host-nation engagement, economic experts for reconstruction and leverage, information specialists to shape narratives, and legal advisors to ensure the legitimacy of ROE.

Modern OOA deployments are not merely military expeditions. They are acts of statecraft under arms.

The Final Lesson

Operation Pawan teaches a hard but necessary truth. Military force without a political architecture becomes a liability. When properly integrated, it remains a powerful instrument of national influence.

The men of the IPKF did not fail. They fought with courage, discipline, and professionalism in circumstances shaped by flawed assumptions and shifting objectives. The nation’s belated acknowledgement does not diminish their service. It elevates it.

By publicly recognising their sacrifice and honestly confronting the lessons, India honours not only the past but also its future soldiers.