India’s reliance on personalism in diplomacy risks eroding the audience’s trust in the country’s long-term strategic stability, especially as institutional checks weaken, raising concerns about future resilience.

The Road to 1962

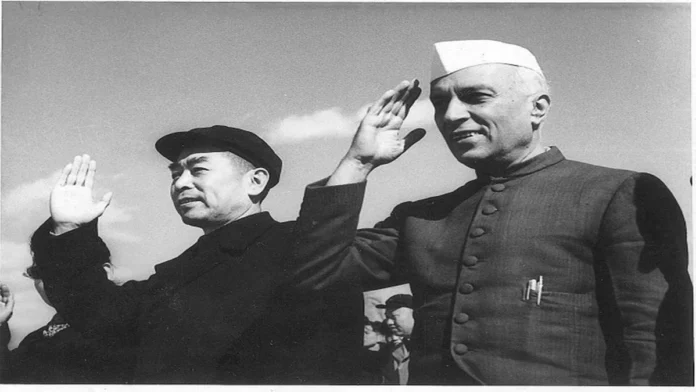

In the decade after independence, Jawaharlal Nehru’s foreign policy towards China was anchored in anti-colonial solidarity, Asian unity, and the belief that ideological affinity could tame structural conflict. The slogan “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai” symbolised this romanticism, projecting an image of civilisational brotherhood even as the two states hardened their positions on Tibet and the boundary.

Key structural triggers to the 1962 conflict were already visible by the mid-1950s.

– The People’s Republic of China consolidated control over Tibet, which India had historically treated as a buffer, and began integrating it administratively and militarily.

– The construction of the Aksai Chin road linking Xinjiang and Tibet signalled China’s intent to secure its periphery, directly clashing with India’s territorial claims in Ladakh.

By 1959, following the Tibetan uprising and India’s decision to grant asylum to the Dalai Lama, Beijing increasingly viewed India as an obstacle to its control over Tibet and as a potential proxy for external powers. Skirmishes and patrol clashes intensified along both the western (Aksai Chin) and eastern (NEFA, now Arunachal Pradesh) sectors, yet Indian political messaging continued to emphasise peace, moral authority, and non-alignment rather than credible deterrence.

Myth of Brotherhood, Failure of Strategy

The “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai” phase was less a coherent strategy than a political myth used at home to justify underinvestment in military preparedness and a reluctance to adopt a hardline stance toward China. Nehru’s government, while not blind to Chinese moves, oscillated between rhetorical idealism and belated hardening on the ground, epitomised by the “Forward Policy” that pushed under-equipped Indian posts towards contested lines without the logistics or firepower to sustain confrontation.

This mix of moralistic rhetoric and tactical brinkmanship proved disastrous.

– Beijing exploited the gap between India’s declaratory policy and its actual capabilities, planning a limited but decisive military offensive to impose a political settlement by force.

– On 20 October 1962, Chinese forces launched coordinated attacks across both sectors, overwhelming thinly held Indian positions in extreme terrain and harsh weather.

The result was a humiliating defeat, the loss of territory in Aksai Chin, and a profound strategic shock that shattered the illusion of fraternal solidarity. The war revealed not only operational and intelligence failures but also the dangers of a leadership ecosystem in which dissenting professional assessments within the military and bureaucracy were subordinated to the Prime Minister’s belief in his own moral and diplomatic leverage over Beijing.

A Pattern of Intelligence Lapses: From Blasts to Border Intrusions

India’s strategic missteps extend beyond diplomacy into a chronic pattern of intelligence failures that personalised leadership has failed to address. The 1993 Mumbai serial bomb blasts, orchestrated by Dawood Ibrahim’s D-Company with Pakistani training, killed 257 despite later confessions revealing detailed plots known to some agencies; siloed intelligence and post-riots complacency allowed the conspiracy to unfold undetected. Kargil 1999 epitomised multi-agency breakdowns—RAW missed battalion redeployments, IB and Military Intelligence overlooked LoC crossings in February-March, allowing intruders to seize 62 miles of heights before an aerial response.

The 2008 26/11 Mumbai attacks exposed even graver fusion gaps: US, UK, and Indian agencies had piles of data on David Headley’s reconnaissance emails, Lashkar control rooms, and plotter communications, yet uncoordinated warnings and overlooked details allowed 10 gunmen to rampage for 60 hours.

Pulwama 2019 repeated the tragedy. General IED alerts were ignored, no specific input on a car bomber was shared despite claims of multi-agency coordination, and convoy lapses led to 40 CRPF deaths.

The 2020 Galwan clashes and Chinese intrusions in Ladakh stemmed from ignored local warnings, disjointed reporting on PLA movements (February-March), and distraction by Hotan exercises, enabling Beijing to seize positions through deception despite India’s border advantages.

Diplomatic spectacles compounded these: the February 2020 Ahmedabad “Namaste Trump” rally projected US-India bonhomie amid rising tensions in Ladakh, blinding leaders to the PLA build-up.

Fast-forward to 2025, and Trump’s tariffs doubled to 50% on key exports, catching New Delhi off guard, threatening 2 million jobs despite prior signals. Over-reliance on the personal rapport between Trump and Modi, forged in Houston, ignored the resurgence of US protectionism after the election. After the fact, major visits or announcements were shaped by political considerations. Diaspora events, leader-to-leader optics, and headline-driven diplomacy are prioritised, while complex policy details, long-term trade-offs, and bureaucratic deliberation are compressed or sidelined.

This model is fragile in at least three ways.

– It increases the risk of miscalculation because decisions are filtered through a narrow political lens rather than broad institutional scrutiny.

– It personalises success and failure, making course correction politically costly and thus less likely.

– It conditions the public to equate national interest with the leader’s image, making questioning of foreign policy tantamount to questioning patriotism.

These vulnerabilities resemble the pre-1962 environment in structural form, when concerns raised by military professionals about logistics and force levels were overridden by political confidence in a forward posture and in Beijing’s rationality under pressure.

History’s Verdict and the Need for Accountability

History does not simply “repeat”; it rhymes through patterns of behaviour, institutional cultures, and strategic myopia.

The link between “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai” and “Ab Ki Baar Trump Sarkar” lies in a recurrent Indian temptation to project moral or personal exceptionalism in foreign policy, while under-investing in complex capabilities, bipartisan consensus, and institutional resilience.

If Nehru’s legacy teaches anything, it is that foreign policy failures, once crystallised in crisis, outlive leaders and haunt the polity for generations. The 1962 military defeat reshaped India’s threat perceptions, civil-military relations, and defence modernisation. It also created an enduring political trope used to delegitimise an entire phase of strategic thought without fully understanding its context.

Modi’s personalised statecraft, especially the Houston episode, may not culminate in a single dramatic catastrophe of the 1962 kind. Still, it carries long-term risks: entanglement in great-power competition on unfavourable terms, erosion of bipartisan support in key partner capitals, and an Indian strategic discourse dominated by image rather than insight. The absence of robust accountability mechanisms today virtually guarantees that any eventual reckoning will, once again, come post-facto and potentially posthumously.

For a republic that prides itself on democratic maturity, this is an indictment. The lesson of 1962 is not merely that Nehru erred, but that unchallenged prime ministerial hubris, sentimental rhetoric, and sidelined institutions are a recipe for strategic disaster. The Houston “Ab Ki Baar Trump Sarkar” moment shows that India has yet to internalise this lesson; the structures of delusion remain, only the slogans have changed.